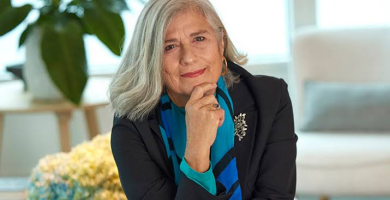

MERITXELL COLELL: “I’d always thought that I wouldn’t ever direct.”

This month we interview the director from Barcelona Meritxell Colell Aparicio who has just released her new film Dúo. A journey to the centre of the couple, with two people who stop being two. We talk about the film with her, but also about her career as a director.

In this new film, Dúo, you continue with the character of Mónica who was also the main character of your first feature film, Facing the wind. What is the connection between the two films and why did you decide to continue with the same story?

The two films are transformative journeys and ask questions about identity and your place in the world. Although in Facing the wind there was this movement of opening and of reconciliation, here what is portrayed is managing to make the decision to continue alone, on questioning who I am, what I am doing here, why, for whom. When a crisis begins in a couple’s relationship, the relationship with the art to which you are devoted, the relationship with a place to which you cannot return, which is the village, because the house has been sold… And this affects a whole series of issues in the main character. We were very eager to continue working with Mónica García, to continue being travelling companions, because I consider her to be a travelling companion, and to continue exploring both other acting registers and this character. Also, how a transformation such as the one experienced in Facing the wind, sharing time with her mother, could resonate in the life that she had left behind. This life in Argentina with her partner of 25 years. How a transformation generates a new crisis.

You lived in Buenos Aires when you studied film. Is that why the film is set there? What is your relationship as a filmmaker with the country?

I studied audiovisual communication at the Pompeu Fabra University, which had an agreement with the Universidad de Cine. I went there to study for one semester when I was 22 years old and I stayed for three years. In actual fact, my career as an editor began there. It was a place of discovery in many senses, in both the professional and the personal and social sphere. It’s a city that I really love and that I can feel inside me. Whenever I have the opportunity to go back to Argentina, I will. But one of the decisions of Facing the wind, that of setting it in Buenos Aires, wasn’t just because of that link, but also due to the transoceanic aspect. It’s not the same living in Madrid or in London as in Buenos Aires, which is really far away. It was a question of marking this distance of the ocean.

In both films there is a type of confrontation between two worlds, one more modern and the traditional world. Why are you interested in this dichotomy?

Because what starts as a confrontation does not end up being one, but rather becomes a much more complex relationship. On the one hand, you feel the distance that is there, but on the other hand there are many points of connection. For example, in Dúo I was really interested in talking, on the one hand, about this relationship of contemporary art with a community art, precisely to illustrate the self, or the egoism of Europeanism, compared with the “us” of these indigenous communities which continue to work based on assemblies, and how this is also present in art. Even more so in a couple in crisis, in which the two or the “us” doesn’t exist any more, but rather is one plus one. On the other hand, I wanted to break with and question this idea of taking art to places where there isn’t any. Where there are the type of tours when you say “let’s take the theatre to”... And to break with this almost missionary idea of art.

There’s a time when one of the indigenous people in the assembly says “We, the Atacama people, are the culture of silence”. In both of your films silence is very important. What is not said. Why are you also interested in this?

For me silence is a very beautiful way of working with gesture, faces, bodies, moods,... and, above all, so as not to give a meaning to everything. This also happens in real life when we sometimes say things which go way beyond what we actually say. A great many things happen inside us or in our relations with people and, sometimes, a look is much clearer than any word. That’s why I’m interested in what’s happening inside not being said, but being expressed through the bodies.

Editing is very important in the film. You began as an editor. Did you already intend to direct or was it just something that happened?

I’d always thought that I wouldn’t ever direct because, when you study, you see the films by the “genius director” who knows everything, is clear about everything and is brilliant. And of course I didn’t (laughs). I thought: “I’ll never be able to direct”. And then, suddenly, on editing films with other people and doing Cine en curso you see that film can be a much more collective, shared, family, craft art and then I could see myself with the strength to go ahead with creations. And now we have Facing the wind.

Going back to editing, it seems that the line between fiction and documentary is very thin in Dúo. Were you clear right from the beginning that you would do it like that?

For me it’s a very fictional film, with a clear fiction but deeply rooted in reality. In that respect, the editing was complex, long and fascinating. We combined the work with Ana Pfaff - with whom I always work on the editing - with working alone to find the film through the material. We needed a certain retreat, to understand what there was, to gradually find it and to thread it together, precisely so that these diaries in Super 8 didn’t clash with Mónica’s voice. There was a lot of work saying yes, no, when, how and gradually seeing how this play between the two universes could be organized. This shared journey and this space inside her to think about it.

Is that why there are lots of close-ups? For example, they are dancing, but we don’t see the dance, just the faces of the two main characters, their expression. Were you more interested in the closeness and intimacy?

There were several aspects to this. It’s a very radical film in which we filmed everything with a 40 millimetre lens. From the beginning it was very clear that we would experience the film from the point of view of the characters. Also because when you’re in the present of your life, you don’t have perspective. You don’t have this open plan of the filmmaker which has to be seen from afar. You’re inside. And, in this respect, we wanted to work from inside and to share both the physical and sensorial and also the emotional journey of these characters. To be with them in this closure which sometimes may appear to be very claustrophobic, but which is also how they are.

In relation to our city, what does Barcelona offer you as a filmmaker?

It’s difficult to talk about Barcelona because I was born here. I can’t understand creation without Barcelona. On the one hand, this film is located outside Barcelona and so is Facing the wind, but my entire circle, the community of filmmakers and friendships, is here. And they are great promoters of creativity. The filmmaker friends with whom I share scripts and editing are here. Or a project like Cine en curso which is centrally established here. All that is the network which allows me to make films.

How did you come to Cine en curso?

I knew the project from its origins, but in 2005 I was in Buenos Aires and one of the reasons to return was actually Cine en curso. It was very clear for me that I wanted to participate in a project like this, which is so revealing and so necessary, to bring film as an act of creation to state primary and secondary schools. Not so much to professionalize or to create filmmakers as to get them to love film, to experience it and to discover the world through film.

And what has working with the students brought you as a director?

I always say the same thing: I wouldn’t be the person or the filmmaker that I am today if I hadn’t joined Cine en curso. On the one hand, it gave me the strength to be a director. To understand this, the possibility of being collective within film. And, on the other hand, doing Cine en curso each year, I have the opportunity to relive that first time, discovering film or the world through cinema. And that’s wonderful. It makes you reconnect with the essence of film and this allows you to renew your energy so that you can continue making films, because sometimes it’s difficult to create films, budgets... You have to wait a long time for subsidies, festivals; there are really very tough times when you could ask: “Why am I making films?” And Cine en curso makes it clear for me why I do it.

What challenges have you encountered when it came to shooting this specific film?

It was a very complex film. Although straight away we had the subsidies from INCAA, ICAA and ICEC. This was a marvellous thing. First we got stuck half way through the film because of the pandemic and then there was the infernal devaluation in Argentina. It was all very complicated. A bit like a defeat, but because of this the other day Mónica, when we were presenting it in Madrid, said that it’s a miracle film. We decided that we were going to finish it whatever the case.

How do you work with the actors? What is your method and more so on repeating with Mónica as you already had a way of understanding each other?

Through dialogue. For me it’s very important to listen, dialogue, share materials, all kinds of correspondence. Not just the script, in the case of Dúo, but also images, songs, the artistic residency that we did with them. How to create a duo together. And to find ourselves from our bodies. When you work like that, with a lot of dialogue, it’s very nice because you always end up finding a common spot which isn’t at all far from what you initially had in mind, but you arrive there from them. For me it’s really important for the actors to portray the characters and never to say or do something that they wouldn’t do. In this respect, we always install the scenarios starting from the people and the spaces and then the camera goes behind.

Is the final result of the film very different from the initial idea that you had in mind?

It’s very different, but you have to embrace the difference. In the end the film has brought us here, it is what it is, and the process has been marvellous. Also what’s really beautiful about Dúo is that it’s led us to a new project. The most rewarding thing about making films is how one project leads you to another and how you gradually learn with the team with which you are working.

Have you already got a new project under way?

Yes, it’s called Lejos de los árboles. Indeed, we are in Ikusmira Berriak, the residency of the San Sebastián Festival. It’s the epic and initiatory journey of Angélica, who is a sound artist who weaves a map of sounds from the Andes. On this journey, insomnia, altitude sickness and the fact that her 98-year-old grandmother is dying in Mexico lead her to a decline. And, at night, the voices, the beings, the stories, the songs and the memories of her native Mexico take possession of her.

We’re now in the development phase, combining it with preproduction. With Dúo we made five research trips, and now we’re making a research trip to Peru. We have a closed version of the script, development subsidies from ICEC and Ibermedia and now we’re waiting to see what happens with the production subsidies to finish defining the schedule.

Photo: Núria Aidelman