MÒNICA GARCÍA MASSAGUÉ: MÒNICA GARCÍA MASSAGUÉ: "LITERATURE AND FILM OPERATE ON TWO DIFFERENT LEVELS: CONCEPTS, PROCEDURES, ETC., AND WE NEED TO BRING THESE REALITIES CLOSER TOGETHER."

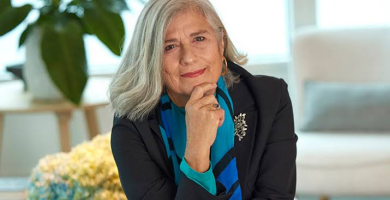

This month we interview Mònica García Massagué, General Manager of the Sitges Foundation – International Fantastic Film Festival of Catalonia, which organizes the Sitges Festival.

We talk to her about the festival and about Taboo'ks, its programme to promote adaptations of literary works as audiovisual projects in which our Laboratory of Audiovisual Adaptations of Barcelona, LAAB, participated this year. A project promoted by the ICUB through the Barcelona Film Commission.

This year you were chosen as General Manager of the Sitges Foundation. Previously you were acting General Manager and you have also been Deputy Director. How did your relationship with the Sitges Festival begin?

My professional relations go back to the year 2004, when I accepted the position of the festival’s Communication Director (a dream come true!). This was only for one edition because I then agreed to be in charge of international festivals in an office promoting films produced in Catalonia. Eleven years later, they offered me the possibility of being the Foundation’s Deputy Director and, four editions later, I agreed to take on the management.

I had previously been a loyal filmgoer, as well as covering the festival as a journalist. I worked in local television and directed several film spaces, so in actual fact Sitges had formed part of my personal and professional life for decades.

Sitges is one of the world’s most important fantastic film festivals. What do you think it is that attracts both the audience and participants to a festival like this one?

Sitges is the world’s leading international fantastic film festival. This status has allowed it to capitalize on an intangible heritage which distinguishes it from any other festival. Great talents have been discovered and have developed in its cinemas, such as Guillermo del Toro, Sam Raimi, J. A. Bayona, Jaume Balagueró, Álex de la Iglesia, Paco Plaza... there are so many names that the fans and participants are aware of this baggage. I believe that each cinemagoer knows that they are taking part in a historical edition and in turn each of them becomes a collector’s item in the memory of fantastic filmgoers. It is curious to note that you are proud when you say “I was present in the Susan Sarandon edition” or “I saw Quentin Tarantino”, etc. Sitges is undoubtedly the source of a unique cinematographic experience.

The festival has been committed to the fantastic genre since it began. Would you say that the festival has given a certain cachet to a genre which has often been considered to be minor?

Right from the beginning, Sitges has used the fantastic genre as an umbrella to accommodate several sub-genres such as horror, science fiction, black comedy, etc. Almost all artistic directors see the festival’s positioning as a strength to attract an audience. At the same time, it allows the focus to be placed on a specific type of film. It is true that genre cinema has been appreciated more or less over time, but the truth is that it now prevails like a language in the hands of prominent directors. This is demonstrated on looking at the programmes of the so-called general festivals, like Cannes, Venice or Toronto, which include fantastic film proposals within their main sections without any kind of reticence.

Actually, one of the things which attract the audience the most is the experience of going to Sitges and immersing oneself in fantastic films, since the whole town participates actively in the festival. How have you experienced the situation of the pandemic? We suppose that it affected the festival in many aspects, but you are likewise committed to face-to-face activities.

Right from the initial design of this year’s edition, we decided that we would go in the direction of a hybrid model. We have closely taken into account what we had to forego due to the health restrictions imposed and, consequently, we implemented strategies such as increasing the repeat showings of the star films (to increase the total capacity); reducing the total number of films; extending the festival until the Sunday, etc.

The result was very positive because we achieved almost all the objectives established. Only the increase in restrictions in the final phase of the festival (three days from the end) limited the good ticket sales, and even so we were able to react quickly and there was almost no impact on the audience.

You greatly increased the viewings of films and series through online platforms. Do you think that the consumption of culture through VOD platforms will change the future of cinema?

This is an old discussion which appeared with the growth in the platforms offered in our country. I think that we are witnessing a historical landmark imposed by a pandemic, which has led us to exceptional circumstances which have limited and shaped a model of consumption, with a necessary increase in VOD.

The short-term future of cinema has therefore already been affected. Cinemas cannot open or have seen their capacity drastically reduced, and their model of economic survival is thus threatened. The increase in the consumption of serialized production in VOD is also favouring one type of audiovisual production over another (feature films, for example), etc. Even so, I believe that they are collateral effects of the situation that we are experiencing and that, in the medium-long term, we will recover the value of the cinematographic experience and the market will end up regulating itself to adapt to a much broader demand.

The festival is not just screenings; there are also many parallel activities such as the professional events of the Sitges Film Hub. What can film professionals find in this hub?

Since 2015, we have implemented an increasingly broad offering for professionals. As well as the programmes in cinemas, Sitges is an exceptional meeting point, the idea being to take advantage of this potential by designing the industry’s own activities or offering the show as a framework of reference for the whole audiovisual sector. In this respect, we believe in a range of activities covering the whole value chain of the cinematographic product and which may be of interest to the different stakeholders: producers, cinema operators, directors, etc. We have moreover focused on the situation of other related cultural industries, such as literature, always keeping the fantastic genre as a differential value.

This year your programme Taboo’ks celebrated its fourth edition within these activities. How and why was Taboo’ks created?

Taboo’ks arose precisely from the idea of expanding the capital of the fantastic genre to other cultural sectors, and we followed the models already existing in major shows such as Cannes, Berlin and Venice. These festivals already have spaces which analyze the links between literature and film from the point of view of adaptation and we saw a space, as is logical, to bring this to our speciality: the fantastic genre. A large part of the publishing industry is moreover located in Catalonia, so Sitges could capitalize on the project in an even more meaningful way.

For those people who do not know the programme, what does it consist of? And, just out of curiosity, what does the name mean?

The name is a contraction of two words: Taboo + Books. The idea was to combine in this programme the more fantastic, dark or controversial side of the genre with literary production. Taboo’ks is therefore an event devoted mainly to film adaptation, but also to any aspect concerning the links between film and literature. From the first edition we included a pitch competition for works which are candidates to be presented to the audiovisual sector, but also a masterclass, round tables, etc., which have allowed aspects that affect both sectors to be analyzed.

Over the editions, have you been able to see how the projects selected were shown in the festival?

We have been able to see those which formed part of the masterclass, given that they already had one foot in production. As for the rest, it is still too early; the path from book to screen tends to be long and the truth is that the current production context is not the best. We also believe that the main milestone to be reached is for the two industries to come closer together in our country, taking advantage of this kind of event, and for the difficulties of the two sectors to be detailed in order to establish smoother work systems.

How many projects were presented this year?

Four works were selected in this edition and, by chance, all written by women. Nothing was established initially, but rather the selection is a good example of the presence of female authors in this genre.

This year you collaborated with our LAAB (Laboratory of Audiovisual Adaptations of Barcelona) programme. You participated on the round table Assessing the potential of adaptations as a moderator. What gave rise to this collaboration and what conclusions were you able to draw from what was said on the round table?

I have been following all the initiatives concerning literature and film for years. One of them was the MIDA, which I think is one of the predecessors of the LAAB and, when it appeared, I suggested to its promotor, Sebastià Mery, that they could participate in that year’s edition of Taboo’ks. They are twin proposals and it is logical that we seek channels of collaboration in order to strengthen the different programmes.

As regards the round table and its conclusions, I continue to think that literature and film operate on two different levels: concepts, procedures, etc., and we need to bring these realities closer together. Indeed, this is one of our pending projects: to train publishers and agents to have a more audiovisual perspective so that they can reliably indicate market needs.

Now that there are many platforms which generate their own contents, do you think that people look more than before at books as a possible source of ideas to adapt to audiovisual for both series and films?

There are many advantages to taking a literary work as the starting point: it is an idea which has been tested; in general it already has a captive audience; the plot is completely mature, etc. The potential of literary production is undoubtedly attractive for audiovisual production and its capacity for innovation and creativity offers examples which are then true success stories. This is the case, for example, of Let me in by John Alvijde or the opening film of Sitges 2020, Malnazidos, based on the novel Noche de difuntos del 38, among many other titles.

Apart from your work with the Sitges festival, you are also a tutor on the Master’s degree in Fantastic Films and Contemporary Fiction organized by the Sitges festival together with the UOC. How did this collaboration arise? And do you think that it is important for you to also collaborate with the educational sector on an audiovisual level?

The idea of organizing a master’s degree on fantastic films is something that I conceived a long time before I joined the Foundation as Deputy Director. I firmly believe in education as a tool for film literacy and, along these lines, the master’s degree is the consolidation of a project to encourage a passion for the fantastic genre. The complicity of Jordi Sánchez-Navarro, the festival’s programmer and director of studies in communication sciences at the UOC, allowed us to develop an extremely complete programme, which does indeed include the roots of fantastic film in literature. For the festival, the master’s degree is a perfect way to capitalize on the knowledge and the documentary capital which the festival creates with each edition.

Have you already put next year’s edition into operation or you still closing this last edition?

Both: the closing of one edition of the festival always overlaps with the design of the next one. The organization of a festival as complex and big as Sitges is a task which lasts 365 days a year. Bear in mind that the festival stays alive through activities worldwide, being the main ambassador of fantastic films and at the same time testing new market trends in order to obtain the best programme each month of October.