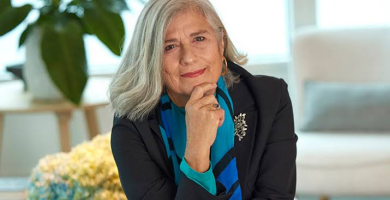

LOLA CLAVO: “As it’s supposed that we all have intimacy, there’s no need to work on it. When it’s precisely necessary to separate your intimacy from the intimacy in the scene.”

This month we interview Lola Clavo, intimacy coordinator, a fairly recent and essential figure on shoots. Do you know what her job is?

What is intimacy coordination?

It’s a new concept which has been in Spain for more or less a year. We’re specialists in intimate scenes. When you have a scene involving karate, fighting or a choreography, you have a specialist. When you have an intimate scene, you also now have a specialist. We have a dual function of prevention, of safety, of protecting the actors and the team from possible situations which could be unpleasant. And, on the other hand, we work on the scenes in a more creative manner, providing ideas when it comes to movement of the body, helping the actors, undertaking research, choreographing. We also bring a lot of things like barriers or garments, for example, to pretend that someone is naked.

They’re not only sex scenes, are they?

Not at all. They’re intimate scenes. Nude or semi-nude scenes. Sometimes what you can see is part of the body of an actor who is more vulnerable for whatever reason, such as a birthmark that they don’t want to be seen. This could be an intimate scene. Or physical scenes between two members of the same family, a father and a son who hug and who have a more physical relationship. We also work on this because it’s still a question of two people who very often don’t even know each other. A character who has a mobility problem, who’s had an accident and is being cleaned in the scene, a doctor who’s examining a patient… These are all very intimate scenes with a high degree of vulnerability. We also analyse the scripts to see, apart from the obvious scenes, whether there are any which could be intimate. Then we talk with the director and the actors to find out what that scene is really going to be like. Then we make our assessment of where we really need to work, not only in the sex scenes. Although the majority are sex or nude scenes.

It seems incredible that this figure has never existed before, doesn’t it?

Of course, but in actual fact that’s the world in which we’ve lived and in which we’re still living, where a great deal of care is taken with some things and others are completely ignored. And as the bodies which have suffered the most from this are those of women, those who’ve been most vulnerable, and as sexuality and the body are things that aren’t talked about. As it’s supposed that we all have intimacy, there’s no need to work on it. When it’s precisely necessary to separate your intimacy from the intimacy in the scene.

Do you work in coordination with the rest of the team?

I work a little with everyone, depending on the scene and the needs. We obviously work side-by-side with the costume department, because it’s necessary to prepare the scene and we need to know what they’re going to wear. We have to work with them to understand, if there’s going to be a nude or semi-nude scene, how we’re going to do it. With make-up if it’s necessary to cover parts of the body like a tattoo. Also always very closely when someone’s more exposed. And then, we obviously work side-by-side with the director and with production. We have to coordinate many times with photography as well, to understand what the sequence is going to be like, how it’s presented, what camera shots there are, how it’s going to be lit. These tend to be the departments with which we work the most. But sometimes, if there is miking, we also have to talk with them about how we’re going to do it. It’s a collaborative effort.

How do you become an intimacy coordinator?

We have different profiles. We always come from something else. Personally, I was in film directing. I studied fiction directing and have a master’s degree in fiction directing. Then I started to make documentaries. I was always very interested in sexuality, in talking through the body, dealing with intimacy. I’ve worked on it a lot as a director. There I learnt a lot about where to place myself, how to try to get things to go well, although sometimes I didn’t do them well.

I was also interested in what is reality and what is fiction. If in a fiction short the sex scene is real, does it become porn? I was interested in the limits. I did experimental porn or ethical porn. And that’s where I learnt the most, because in the end it’s a medium in which you work the most collaboratively. The projects are created collectively. You talk with the actors, but they decide what they want to do and what they don’t. You have an idea. And it’s a question of all coming to an agreement. There I learnt about consent, about how to communicate, how to respect, how to give people space. And after this, I realized that these subjects are worked on in independent fiction, but in mainstream fiction we see terrible intimate scenes. Why? What can we do? I began to give workshops and courses above all for directors on writing, analysis and preparation of sex scenes. And when I was preparing one of these courses, I found this figure. “How come you haven’t seen this before?” I asked myself. It’s perfect for me; I’m really interested. Because as well there are things that I know, but others that I don’t. I began to search for everything I could on the subject. There wasn’t much; this was back in 2019, 2020. I listened to interviews, read articles, signed up for all the online courses I found.

There is some official training, but very little; it’s almost all in the States and is very expensive. It’s very difficult to get in; you have to have a lot of experience and a good CV. They want to see what career you’ve had. It’s training which takes things from many different types of training. We do things on work with the body, the culture of consent and how to understand it and how to guide it; we work on trauma, the dynamics of power, anti-racist courses, courses on sexual diversity… There’s some training in the States, the UK and South Africa. In Europe I only know about the UK.

What do you most like about your job?

Knowing that you’re making a small change to life, that you’re improving the experience of a shoot for many people. That you’re helping a situation, which is often very stressful, complex, or which could give rise to a great deal of anguish or trauma, to go well. When we finish shooting and an actor, director or someone from the team comes up to me and says “thank goodness you were there, you’ve helped me a lot, I’m much more at ease”. And moreover you want the scene to be incredible.

What are the main difficulties that you encounter? Do the teams adapt well to this new figure?

There’s a bit of everything. I haven’t had any very bad experience, and I hope I never do, but I do have colleagues who have. Although you might have some idea and you decide to hire an intimacy coordinator, in actual fact you don’t know how they work. It’s very difficult to get people to understand well what we do and how they can use us. Often they don’t let us do our job, but they don’t even realize. It’s difficult to get someone to understand that they’re not doing something properly without having to tell them. Because also you understand that they’ve done it like this for the whole of their life without even realizing. They are very subtle things. Everyone knows that, when there’s a nude, we have a small set that everyone respects, but there are small details that it’s more difficult to see. People will gradually understand it and experiment thanks to the experience of working on it little by little. After the shoot people often say to me “oh, that’s great, but I didn’t think it was going to be like that. I thought you were just going to do that, or that we weren’t going to be involved in these things. That you were just there to watch over things”. There’s this idea that we are the morality police and that’s not at all true. It’s more the opposite – we’re there for there to be more explicit scenes.

Do you think that this figure is sufficiently present on shoots here?

As far as I know there are five of us in Spain. We’ve created an association. Other people are training; there are a lot of people interested. In Catalonia, I think I’m the only one. I also work with a girl who’s training; she sometimes helps me, so soon there’ll be two of us. There are more people in the rest of Europe. Apart from the United Kingdom, where there are more because they also use them a lot in the theatre. But I do know that there are one or two people in Germany, in France, in Latvia, in Italy. They exist, but there are very few.

You are a co-founder of RED ICIE – International Network of Intimacy Coordination for Show Business. How and why was this organization created? And what difference is there with the association of intimacy coordination professionals of Spain?

RED ICIE is international and we founded it together with the coordinator María Soledad Marciani, who is Argentinian but lives in Italy. We started talking because she found me online. There were very few of us and we simply had a zoom meeting to share experiences. All this comes a lot from English and from American culture. And there are things which didn’t work for us, for example about language. How can we talk about this with our language and in our industry? RED ICIE was conceived with this idea of sharing experiences and trying to create thinking - from what is Latin, from Latin America and the south of Europe - about the subject. Because working in the United Kingdom or Germany isn’t the same as in Italy or Spain.

The association arose from this need. We were all from the network, but there are people from other countries there. And in order to be able to align prices, make our demands known, provide training, give talks… we created an association of professionals. There are very few of us, but we think it will grow and that it would be good to be organized.

You also provide training related to intimacy and sexuality in schools such as Escac and La Casa del Cine. Are students more aware of the importance of this figure?

Of course. There are things that they’ve already assimilated, but it depends a lot on the person. There are people my age or older who want to learn and change. What students do have is the desire to have new information; they’re very open to being taught things. And you can see this; they’re not already working on their film, but rather they’re in class, and they soak up everything that you explain to them. I like doing this a lot because I think that, when you assimilate certain things, you make changes which you take to your professional and personal life. Like when we do things on consent, understanding what it means to say no to someone. We do exercises of this kind so that they feel it in the flesh. We talk about the dynamics of power and I explain to them what power is, that we all have it, what it means for someone to say no to someone with power. We talk about all this which has nothing to do with films, but which has everything to do with them. Because, in actual fact, it’s very hierarchical.

If we want to break these dynamics of abuse, we have to understand where they come from. We can’t just say that he’s a bad person. There’s a whole system which makes this happen. When I offer training, beyond the fact that we then do shooting practice, the first thing I try to get them to understand is all this. And it works. Even if they are then clumsy in the shoot and they do some things wrong, it’s something that they take to their professional life. Students write to me in the following year to tell me that they’re preparing something and they have a scene of abuse or an intimate scene and they ask me to take a look at it or if I know someone who can do the intimacy coordination for them. They quickly become very aware of it and integrate the role of saying “I need someone to help me”. Because until now students were left to find out the hard way. It’s a great deal of responsibility.

You collaborated with the Netflix series Smiley which was shot in Barcelona. What was the experience like? Being an American company, is this figure more present?

Netflix has had this figure integrated in all its worldwide productions for some time now. If you make a series for the platform, you have to have intimacy coordination. It doesn’t come from the local production company; this might sometimes be a problem. In the case of Smiley, not at all. They welcomed us with open arms, made it really easy for us, and let us rehearse. But you’re always fighting for them to give you time to do the exercises with the actors, to warm up. For the same reason, because they don’t know how to plan you within the shoot. They give you five minutes and you tell them you need 20. This happens a lot in big productions. There was a bit of a rush in a series like Smiley because they had a lot of sequences on the same day, but the experience was very good. There was a fantastic environment on the shoot. The team was run by the Madrid girls from IntimAct, an intimacy group, but as they were there and they couldn’t always come, they called me. And some of the days I went to the set.

This role is increasingly integrated in the industry. If you’re preparing a series, in which there’s a sex scene, they call you. For example, it happened to me with a very young actress and, although it wasn’t something very explicit, she’d never kissed anyone on screen. They think of us more quickly. It’s important for us to join the project as soon as the script is more or less closed. In my case, I analyse scripts and offer consultancy; I can see whether the scenes have something which I can suggest to them just from the script. And otherwise from pre-production, of course. Our work begins before the shoot, in order to prepare everything so well that it all runs smoothly. No one should realize that we are there and if there’s any unforeseen circumstance, we can make the changes quickly.

Has television adapted better than film to this figure?

The fact is that many series are made. A lot of content and the shoots are longer, although not always. I’ve only worked on series, on one short and on a video clip. It would also be interesting to adapt it to advertising, to perfume ads. They’re normally models, not actors, and they tend to be very young. And as they are models they’re used to being naked, but a catwalk or a photo session isn’t the same as a shoot.