Ferran Herranz: "it is very strange for a film from the independent film circuit which begins in Cannes to also end up with the American Academy awards."

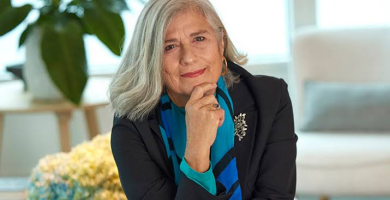

This month we interview Ferran Herranz, co-founder of the distributor La Aventura Audiovisual, responsible for us being able to see Parasite by Bong Joon-lo, the big winner at the Cannes festival and at the Hollywood Oscars. We talk with him about the film’s success but also about the work of a distributor. Note: this interview was conducted before the State of Emergency came into force because of Covid-19, and therefore some questions refer to the previous situation.

When was the distributor founded and why did you embark on the adventure of La Aventura?

The distributor’s two cofounders, Jose Tito and myself, both had experience in distribution. However, at that time we were in a production company, Nostromo, and it was difficult to find our place on the distribution side. It was a time of a very deep crisis in which the distributors could not take big risks. There were moreover very many interesting films which were not being distributed in Spain. There we saw a good opportunity to get hold of a series of titles, to begin to exploit them and to start very slowly with very sustained growth.

Did you decide on the name La Aventura precisely because of what you mentioned about the difficulty at that time?

It is because of Antonioni’s film, although it was like starting an adventure when we set up the firm at that time and gave it that name. People said it a lot because at the time the economy was all screwed up. We decided on the name of Antonioni’s film which sums it up so well.

Normally we know the role of other agents in the sector, such as production companies, but maybe the work of a distributor is not as well known. For someone who doesn’t know what it is, what exactly does a distributor do?

In the film industry we are exactly like a book publisher. The thing is that, because of the terminology, we always associate a distributor with someone who takes physical copies of something and delivers them somewhere. A book distributor delivers books to bookshops, but does not publish them. On the other hand, we publish and distribute. We look after the whole chain. We are not sufficiently well known because the logo does not make an impression even on a mass level. When people have been to see a film, they don’t care whether they’ve seen the logo of Warner, Universal or another. They just want to see good films. It is, however, possible to establish a brand which gives a certain amount of confidence and which has a certain following. But this is nothing compared to the people who are truly important in films, who are those in front of or just behind the camera. The level of followers that we can generate or of impact in the news about us is very low. However, we continue to be necessary to bring films to cinemas or the television, although less as regards the big operators of video on demand by subscription which have now appeared in Spain. Therefore, although we are not well known, we still have a place and that is what is most important to us.

Have you been affected a lot by the arrival of these platforms?

A great deal. In the end a distributor is an intermediary between the producer and the final viewer. The big platforms have been able to establish branches in all countries, to purchase worldwide rights or in many territories. They do not need to have intermediaries in each country and obviously if they can manage without, in a liberal world such as the present one, they will do so. This has made us focus on a product that you need to pamper, which with a platform would be somewhat undermined. To make it clear: the Grand Prix of the jury at the last Cannes, Atlantique by Mati Diop, is an excellent film which Netflix had worldwide on its platform, since they bought it, but which did not have any echo. Meanwhile, it would surely have found its place in independent film cinemas worldwide. The film did, however, run the course that the producers wanted in the end. We cannot say anything else. However, with films which still choose this traditional model of exploitation in cinemas and the rest of the very interesting platforms such as Filmin or Movistar, we continue to be here to be able to bring these films to these other windows. Not everything is Netflix and other platforms.

With Parasite, we were very lucky and it will surely allow us to be quite a bit more relaxed for a few years, but the future panorama is difficult. Before releasing Parasite, it was not very encouraging and we did not see a very bright future. Although we are still necessary as intermediaries between the producer and the viewer, at the same time our part of the cake has become much smaller and we are a large number of companies for quite a small piece of cake. We therefore understand that, in the coming years, this trend will become worse, and maybe we will be left with the people who have managed to do it in a special way, so as to say.

What is the day-to-day work like in your distributor?

There are three very intense points in the year which is when you go to buy and which we could summarize as February at the Berlinale, May in Cannes and then the summer circuit which consists of Venice, San Sebastián, Seville,... You see films which may interest you and which you can negotiate everywhere and in all festivals. Also, when we are not travelling, we are always preparing the next release and the next films that we have to deliver. It is like a publishing house, in the end, with an established calendar, a series of jobs involving marketing, translation and all kinds of decisions which have to be taken and muddling through.

How do you choose the films that you are interested in distributing?

It’s a lot to do with us liking them and their directors seeming to have talent and be strong. From there on, you need to have the perspective of a viewer, and we begin to think about how we would take these proposals to the people. For some time, the success of Parasite will allow us to be less confined. Not just to detect films which we find interesting with a view to them being profitable with the audience but also to really believe in films which we can pamper and expand in some way, always along the quality lines of the main festivals. They are films which have been in Sundance, Berlin, Cannes, Venice and San Sebastián.

And why did you acquire Parasite? What motivated you about this film?

We had already been in charge of a previous film by its director, Bong Joon-ho, which was Snowpiercer. This was really the first important title that we were able to handle. It was made in 2013 and we released it in 2014. We would be interested in anything that Bong Joon-ho did. He did the next film with Netflix, Okja, which was not unanimously very well received. Also, when he announced a local Korean film, it did not initially generate huge market interest in the first screenings. A small distributor like ours can read the script and access the project without too much competition.

Did you ever imagine this success?

Impossible. Even when it won the Palme d’Or at Cannes this was already well above our expectations.

What do you think is the most attractive element about Parasite which has captured audiences worldwide?

In the end it’s a commercial Korean film. The Koreans have been making extremely high-quality commercial films for many years. Obviously, not all the films are as good as those of Bong Joon-ho or Park Chan-wook but they have an enviable industrial fabric. If you add to this way of directing and of creating films the talent of Bong Joon-ho, with a story which seemed local because it deals directly with the issue of poverty in Korea, but which in the end is very universal, in a world so, so full of inequalities that are moreover increasingly big. There was also an incredible alignment of the planets, because it is very strange for a film from the independent film circuit which begins in Cannes to also end up with the American Academy awards. But this film fell on its feet; it delighted and caught the attention of audiences everywhere. This is also unique. You only come across one case like this in many years.

What was the repercussion of the Oscars for you and for a film like Parasite?

Before the Oscars ceremony, the film was already a resounding success for us. It had already achieved 500,000 spectators, which represented €3m at the box office. And, since it won the Oscars, this has shot up.

Do you think that this success will mean that more Korean and therefore Asian films will be seen?

The main Spanish festivals and the main television channels or platforms have organized cycles and specific things and, obviously, for a couple of years people will be more interested and they will find really interesting things. But, how many will remain? Because we don’t think that we are now going to discover 300 Korean films which will change our lives. Maybe we’ll discover a maximum of 10, 12 or 15. There are a lot of good films everywhere in the world but it is clear that they are now a fixed point on the map. In what position? We will see. Bong Joon-ho or Park Chan-wook will not have any problem with their next projects, but the majority of Korean films are very local. There are five or six films each year there like Ocho Apellidos Vascos (Spanish Affair) here. They have mass audiences in the cinemas but, at the same time, they are not the easiest films to export because of the touches of very specific humour, the impact on the drama in certain sequences, how they see violence... We could say that Parasite was very, very universal, but it is not that easy to export the rest of Korean films.

You have a good catalogue of Asian, not just Korean, films. Why this interest in this type of film?

It’s purely a matter of quality. No one in Spain is distributing Hong Song-soo, the main author of Korean filmmaking. He has just won the award for best director in Berlin. And he is someone with a great reputation in Europe. No one was distributing him here and we said: “That cannot be right” and we have handled six or seven of his films. And also The Handmaiden by Park Chan-wook or The Wailing by Na Hong-jin were films with an amazing quality and which we wanted to bring here, although they did not achieve spectacular figures, rather the opposite. This was, however, part of the catalogue that we were delighted to nurture and we could afford to do so.

You also have a good portfolio of independent horror films which maybe other distributors do not handle. Why do you have this interest?

It’s also a question of taste and because bigger distributors with higher overheads cannot afford to handle films with a low margin. We have always remained very small, with a very small structure, and we can afford to add up small margins. In this case, they were films by people that we liked and which, again, absolutely no one was handling or which competed in the official section of Sitges and other festivals and which then appeared on some platform a long time later. We take some of them to the cinema and we publish them physically to enable the fan base and collectors to access them.