ACAPPS: “Not being able to hear shouldn’t be an obstacle, especially now that so many technological resources exist”.

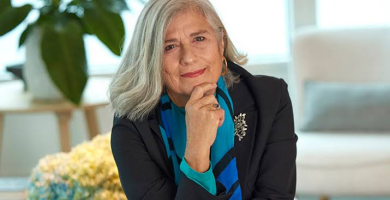

This month we interviewed Raquel Díez Ventura, coordinator of the alliances, participation and volunteering area of ACAPPS (Catalan Association of Deaf People and their Families), who led the organization’s Apunts en Blanc project, and Andrea Amouzouvi, who has a degree in Psychology from the UNED and a master’s degree in Employment and the Labour Market from the UOC, and Eduard Folch, a graduate in Finance and Accounting from the URV. Both of them appear in the documentary Apunts en Blanc.

How was ACAPPS created?

Raquel: Some 30 years ago, because a group of families with deaf children didn’t consider that the rights of their children were recognized in the other associations which existed at that time. It was created to fight for the rights of their children, so that they could communicate with spoken language. We explain this to establish the difference with the collective imagination which often thinks that deaf people only communicate using sign language. The truth is that the people we deal with are very diverse: with hearing devices, cochlear implants and hearing aids, and who communicate orally with lip reading and other technical aids. Indeed, 98% of deaf people communicate with spoken language.

The association has gradually grown, gained momentum and now we offer different help services to all deaf people at any time in their life, from recently diagnosed children to people who become deaf at a later stage of their life. Our services include speech therapy, psychological assistance, labour advice when job-seeking, support with work placements, and the whole business department, devoted to raising awareness in the business and association fabric to foster employability. We also work on the cultural level, like the documentary which is half way between this service of alliances and of making culture accessible to deaf people.

In the audiovisual sector you offer a subtitling service. What does it consist of and what is its aim?

Raquel: We have an accessibility service which currently has several projects under way, such as subtitling videos for cultural organizations, to which we offer the possibility of subtitling material that they use for exhibitions - for example, in museums - or to screen a video. If it isn’t subtitled, we do it free of charge to make it accessible to deaf people. Beyond that, we want to advance towards universal accessibility, to be able to see a video without the need to hear it.

The other project is aimed at companies and cultural organizations: we subtitle short videos for the social media. It arose from the huge demand from companies which upload videos to the Internet. The general population increasingly turns off the sound and, if they’re not subtitled, they’re not accessible and we lose part of the audience. This project arose from the need to have a higher audience, and from the demand that to be accessible it has to be subtitled.

We also offer training so that you can learn to do it. We can do it ourselves at a time of need, but we give you four tools so that you can learn and your social media can be as accessible as possible. The training lasts five hours: one morning. The aim isn’t for you to become subtitling professionals, because there are already professionals for that, but we give you four tools to be able to do it. Because we know what subtitling is like for deaf people. It’s not just transcribing and that’s it. There’s a series of parameters.

As part of your effort to request more accessibility, you produced the documentary Apunts en Blanc. How did the idea arise?

Raquel: ACAPPS, right from the beginning, always had a network of deaf university students who were demanding accessibility in the classrooms. They’ve always carried out actions, held meetings with universities - above all with the help services for students with a disability -, drafted reports, asked what the needs of these students are, how to reserve the first rows. After the pandemic we revived the group, which had come to a standstill. Many of the young people left, because they weren’t so young or they weren’t at university any more. A new group of 14 young people entered. Some stayed, like Andrea. And they were really enthusiastic, saying that they had to go one step further than what had been done so far, that they wanted to raise their voice, and do something that would have an impact beyond a written report or a meeting, something that would have an effect beyond universities. That’s why we want it to go beyond the university audience, so that it stirs consciences, and is an accessible cultural product. We want it to have accessibility right from the beginning, from the script to the production and postproduction.

Andrea: We really needed to talk about what it meant for us to go to university, bearing in mind that we have difficulties. We were excited about the project of making a documentary in which we could explain it. We held various sessions over the months. There were meetings and we talked about what it should include. We wanted to raise awareness, above all among the teachers who give the classes, but also among the entire university community, so that they could make it easier for us to study on an equal footing. The idea is to make it easier for those who come after us. Because, in the end, being able to study and be successful at work is as important for us as it is for any other person. Not being able to hear shouldn’t be an obstacle, especially now that so many technological resources exist. Sometimes, it’s just the fact of not turning while they speak.

Edu: And we have to look to the future, to be able to have the best accessibility for us. Our experience with the filming was very good. It’s like a family, and it all turned out very well.

Normally, people think about accessibility once the audiovisual product is already finished, when the film’s already been made, but with this documentary you worked on it from the initial script. What was this approach to the script like with the writer and director Xavier Borrell? As participants, did you prepare the script? And what was the experience of joining before filming like?

Andrea: In the meetings with the director Xavier Borrell, he wanted to get to know us. Not everyone knows deaf people and he didn’t know what it was like. We held meetings with all 14 of us and talked about the real situations that we encountered not just at university, but also in life in general, so he could get an idea of which situations he could use, as they also occur at university. Sometimes, the fact that we suffer from non-accessible situations is so internalized that we consider it to be normal and we had to recall and remark everything that shouldn’t happen, so that he could see the extent of this problem and be able to convey it or transform it into situations that could be transferred to audiovisual.

The idea was to do it through brainstorming with each person, concerning the situations that we experience in life, in the family, in the street, studying, at the cinema, wherever. And to create guidelines and see what to highlight more in order to generate a greater impact in people, so as to make our daily life easier. To see how we could convert this into a dialogue, with actors or creating situations, so that the problem we wanted to talk about could be seen.

Raquel: Apart from this co-creation that Andrea explained, we also had sessions with professionals from the EMAV who are experts in accessibility and explained to us how to try to include accessibility starting from the script. They told us: “For a script to be accessible for a deaf person, you must bear in mind that we’ll provide an audio description”. If in the script, instead of putting “Pepita, eat the sandwich”, you say “Pepita, eat the omelette and cheese sandwich”, you’ve already described it because the actor said it, and the audio description won’t have to include it.

If we have to include an audio description, we’ll have to leave some spaces silent, because at some time there has to be a voice-over for blind people, for example. In our case, it must have subtitles below, and the acoustic sounds at the top, and it must have the icon when there’s music or a bell, the audio description of what’s happening. And they said to us: “Think about what the shots will be like so that the subtitle can be seen well and look nice”. Often those who are doing the set design think of everything, but they don’t think that there’ll be subtitles. If you have a close-up and you put subtitles it may cover the lips. One of the things we did in the documentary was to interview the young people. The shots had to be more open; they had to have space to be able to put the subtitles.

When shooting, what problems did you encounter and how did you do it? Did you have any experience within the audiovisual world?

Andrea: No, I didn’t have any experience of this type. And it was great fun to try. There were some scenes in which we depended on acoustic signals to do certain actions and here we were a little concerned, because we saw that they didn’t coincide in time. And it would be awful if everyone did the action, but not those of us who didn’t hear well. Here I’m talking about when there were extras.

In my case, a friend came as an extra. She’s deaf, an oralist, and has a hearing aid, and we both needed some support so that we knew when we had to do the action. And a specialist from ACAPPS, who also participated in the project, helped us. She placed herself somewhere where she wouldn’t appear on the camera, but we could see her and she could give us a signal with her face, to say: “Now”. And we had to get up and do the action. Or the part of questions on the set, which was a little dark, if someone didn’t understand well, we asked them to repeat it. There wasn’t any problem; they adapted fairly well.

Edu: Yes, I had problems in an interview; I was lip reading and asked them to repeat when I didn’t understand.

Andrea: As we were all in the same situation, this gave me peace of mind, but I imagine that being on a shoot where everyone can hear would make me very anxious. Because people say their part of the script, but if you don’t know what they’re saying it’s more complicated to know when you have to intervene or what you have to say. There has to be more teamwork. And above all it must look good on the screen. It must have a professional appearance, but as we were all people with the same needs it went very well.

Raquel: We were conscious of the problem, but we also missed some things. We shot a lot of scenes at the UAB, and we went to the cafeteria for lunch. And Tània, who was next to me, said: “Let’s go; I can’t stand the noise there is here indoors”. Processing so many voices, so much noise and nerves. We didn’t think to look for quieter environments. It would have been appreciated due to the acoustic overstimulation.

As a viewer, what difficulties have you encountered on accessing audiovisual content and what do you think can be done to improve it?

Edu: The subtitles should be more precise. And it’s very important that they’re in different colours, to know which actor or actress is speaking, to be able to differentiate the person. And also the background of the subtitles should be transparent, so that you can read better. And a suitable size, so as not to cover the video too much.

Andrea: It’s a little difficult to know who’s talking when there are many people on the screen. It’s important to know who said what, because otherwise you don’t understand the plot. It must be high quality subtitling.

Raquel: There’s a subtitling regulation. And, normally, what we tend to see is the translation of the films. In Netflix, Filmin or wherever, if we put subtitling in Spanish, this isn’t subtitling for deaf people. The characters must have different colours; it would be necessary to subtitle when there’s acoustic noise in the environment, etc. These things aren’t done.

You’re trying to get the documentary shown. Where can we see it?

Raquel: We weren’t sure whether or not to put it on YouTube with open access. At the moment, there isn’t open access. We show it at universities and schools that ask us for it. ACAPPS goes together with one of the young people, and we provide a presentation and a short debate. We also presented it at the Inclús festival. And we’re thinking about how to open it up more. It’s also been shown twice on the betevé television channel, and in a programme on La2 - which is called En lengua de signos - they did a report about us and showed a few scenes from the documentary. But if someone wants to see it, we send them the link or we ask them to help us create a group to screen it and hold a debate which is what we’re interested in, although we’re open to everything.

Do you think that people are aware of the problems of deaf people?

Andrea: Unfortunately, no. I don’t know why this happens with deafness, which is very different from other disabilities because it’s invisible, as we always say. Increasingly, with the progress made to rectify a hearing impairment, when you meet someone it’s difficult to know if they’re deaf. There are many grades, types, there are different stimulations, environments, and they make the way in which you defend yourself in life change a lot. People find it very difficult to repeat. They’re annoyed when we ask them. As if we hadn’t paid attention or it was a whim. They also find it difficult to articulate. If they talk quickly, we can’t read their lips; we can’t associate it with the sound of the voice and understand. It’s a constant effort and people don’t understand that, if they don’t facilitate things, it’s also a difficult for us at work and socially. If there are groups, for example, starting from four of five people, I find it difficult.

Because people talk among themselves, and they don’t understand that if they do this we get lost very easily. We need to take it in turns to speak. It’s not easy. We have to ask people constantly, as if it were a favour, when just with a little accessibility… And for them they just have to make the effort for a moment, while they share this time with us. But we’re always deaf, in any circumstance, and that’s why it’s difficult. Any project is welcome which raises people’s awareness.

Edu: With the documentary we’ve begun to raise people’s awareness, but there’s still a lot of work to do in the future. For example, last week the documentary was screened in a company where I work. And you can see how deafness is experienced at university and in daily life. Then we were able to work together and do things differently to how they were before.

Raquel: That’s what makes a difference, the fact that we can experience the response so soon. Edu showed the documentary to all the staff of the company and this week he noticed that they addressed him differently, when they’ve already been working with him ever such a lot. We need this impact that we obtain with the documentary. It’s true that it does have a certain effect: we try above all for it not to be tear-jerking or about feeling sorry, but we do want it to touch people’s conscience.