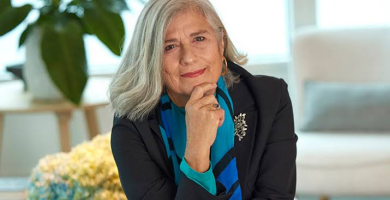

SARA ANTONIAZZI: "What I’m most interested in is for people to know these films, not for the specialists to talk among themselves."

This month we interview Sara Antoniazzi, who has a Ph.D. in Modern Languages, Cultures and Societies from the Università Ca’ Foscari in Venice, and a Ph.D. in Humanities from Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona. She is the author of the book Barcelona en pantalla, una ciudad en el cine.

When did your passion for film begin? Because your qualifications aren’t related to this sphere at all.

I know, and people are constantly reminding me. In Italy, to study at university in the sphere of Spanish or Catalan you need to have publications in very specific spheres of culture, and there aren’t any on film, although there are on literature. I should write more on literature, but I like film and the arts. It’s a passion that started in my family with my parents. They loved going to the cinema and, above all, classic American films. The old comedies, romantic films, Hitchcock,... When I was little, you could still see them on television. There was one each day. Now we have platforms and there’s still something, but let’s say that here in Italy on public television (I don’t know about Spain) you can almost never see them. Christmas films still resist. They show them every Christmas.

This passion increased when I grew up. I was also lucky to be a teenager at a time when the Internet was just beginning, because I could search for all the films I wanted. Especially for me, because I live in a very small city with 40,000 inhabitants. It’s not Barcelona. There, if you wanted to see a film from the past, I’m sure there were big shops where you could find everything. Not here. I remember that many years ago I wanted to see films by Bergman and when I went to ask they said: “oh, yes, Ingrid Bergman”. And I said: “no, the director”. They didn’t have anything. The same happened to me with a film by Truffaut, Fahrenheit 451, and they wanted to give me the film by Michael Moore Fahrenheit 9/11. This is what it’s like in a small town or city. The Internet changed everything. It was like a new world; a universe opened up.

Why did you decide to write this book Barcelona en pantalla, una ciudad de cine? And what links you to our city?

In actual fact the idea was the project for my doctoral thesis. At university, we do three years and then another two years of specialization. In the last year I followed a course by a Catalan lecturer called Enric Bou entitled “Barcelona in literature”, which also spoke a little about film. I had the idea of doing Barcelona in film. I also lived in Poble Sec and, to write the book, I studied the history of the city, also very interesting from a town planning point of view. For example, everything about Cerdà. Then I obtained my Ph.D. and a lecturer who is now in the UPF called Jaume Sobirana came to Venice for a course on Catalan literature and poetry. This gave rise to my passion for the Catalan language. I decided to learn it. My encounter with these two courses meant that I decided to continue with the subject of Barcelona and film and to learn the language which is crucial because, if I couldn’t read the language, I really wouldn’t have been able to do this research.

You mention that the lack of presence of Barcelona in studies on cities in film is surprising bearing in mind that the city was a pioneer in film and promoted its development. Why do you think that the city hasn’t been studied more from this perspective of film?

Above all, specific moments of the history of Barcelona have been studied. For example, there are fantastic studies by film historians such as Palmira González on the birth of film in Barcelona or very good studies on the last part of the history of Barcelona and film after the Olympic Games. And studies continue to be published now on this post-Olympic era. And also the civil war has been studied quite a lot for obvious reasons, but I think that the part about the Franco regime in relation to the city of Barcelona hasn’t been studied so much. I think that it’s also a problem of having access to the films; many of them aren’t well known or are minor films and in actual fact aren’t that good. The majority of those which were made during the Franco regime were silly comedies, the films of developmentalism, things like that. Maybe that’s why there’s not much interest. Because then there are specific periods which have been greatly studied. Barcelona and detective films or film noir in the 60s, for example. What I’m most interested in is for people to know these films, not for the specialists to talk among themselves. And I hope that from this point of view the book is fairly accessible to people who are not film historians, but rather normal people.

Has Barcelona as a film setting shown the urban development changes in the city?

Yes, in some cases very clearly, for example in the film that I talk about in the book, En construcción by José Luis Guerín. This film dissects and addresses precisely this subject a lot. It demonstrates this change. Then, in general, films have shown these changes in an indirect manner. You have to go and search for them in the film. You have to look at the urban landscape carefully and find what’s changed. I love this; it’s like being an archaeologist, but of images. There are people devoted to this. In England, for example, they’ve done this with some neighbourhoods of London. They searched, analyzing films and they’ve seen the changes in streets and buildings. Also in Liverpool. There’s a whole academic project there in which they’ve searched for the changes using the films from a specific period. But, in actual fact, in most cases the film uses the places as a setting; it doesn’t have this desire to show the changes. Although there are authors and directors, like Wenders and Antonioni and Guerín himself, who are directors who are obviously interested in documenting the changes in the landscape. But these cases are exceptions.

Do you think that there is a before and after All About My Mother by Almodóvar for the city of Barcelona as regards films?

Yes, because it was a very successful film, especially in the States. And it generated a great deal of interest in the city and in filming in Barcelona. Before Woody Allen, and moreover Almodóvar’s film is on another level. All About My Mother is a very good film. The BFC already existed and then it’s also worked a lot to increase and maintain the stability of this interest. It was crucial in presenting the city to the public from other countries.

You chose two lines of research: urban archaeology through film and film as an influence on our perception of the urban space as a result of urban development transformations such as the 1992 Olympic Games. Why these aspects? The first part of the book, which talks about more unknown films, is more striking than the second part, which deals with more well-known films. Isn’t that the case?

I think that the vampirized Barcelona is the best part of the book. On the other hand, the last part of the book is the least interesting for me. They are also the aspects least studied by me. As a researcher, the more historical part which is more about the past is the part that I prefer and I think you can tell that in the book. The more contemporary part is also interesting. You could say that it’s films as a marketing instrument. Although, in actual fact, this has always been the case. If you watch films like Roman Holiday with Audrey Hepburn, that was also marketing. It’s not a present-day invention. But, in the case of Barcelona, in this respect it’s particularly interesting that Vicky Cristina Barcelona received money from different institutions precisely with this goal. This attracts my attention above all because it’s also a very well-known and important director in the history of film. Normally he makes art films which are not intended for the general public.

Was it difficult for you to find material or to see all these films from the beginnings of cinema?

I always went to work at the Filmoteca in Barcelona. They do an incredible job; it’s a fantastic place and you can find everything. Not just the films, but also bibliography, magazines,... on films in Barcelona and films in general. Now that I’m in Italy, for example, the problem is having access to the films or the documents. It’s more difficult. It could be promoted. And also what happens with the old films from the beginning of cinema: there are some films which have been lost. For example, one of the films I’m talking about, the one by Fructuós Gelabert, Salida de los trabajadores de la España Industrial, which is from the beginning of film in Spain and Barcelona, has been lost.

The other problem is that very often they can be found, but they haven’t been restored or are in quite poor condition and then it’s also difficult to imagine, when you see the films, what it was like with the colours, etc. For example, I haven’t looked for a while, but there are fantastic films from the history of Catalan cinema like Los Tarantos by Francesc Rovira, which is wonderful, which can’t be found and can’t even be bought on DVD. I don’t think it’s been restored or if it has it doesn’t exist on DVD. You can only buy it second hand if you’re lucky. That isn’t good. It should be mentioned that there are true masterpieces of Catalan film which aren’t available for everyone. And they should be more widely available. For example, I showed a friend of mine who is an American film critic the sequence from Los Tarantos in which Antonio Gades dances in the Rambla, which is fantastic, and he told me that it was wonderful and I explained that it was a film by Rovira Veleta, but that you couldn’t find it to watch. There are many Catalans who don’t know this film. More attention should be paid to this. For example, the same happened to me with a film that I mention in the book, Life in Shadows, which is also fantastic, but before it came out on DVD for years it was a real ordeal to see it. Luckily it’s been restored and it’s now fairly well-known, but more should be done. It’s a film from 1963; there’s still copyright. It’s not just a question of digitizing, but also publicizing and making it accessible.

At the end of the book you talk about films like All About My Mother, L'Auberge Espagnole and Vicky Cristina Barcelona to discover the picture-postcard Barcelona and Biutiful and En construcción for a more real Barcelona. Why did you choose these films?

It was quite a banal decision. They are the films which have been most successful, which are most well-known, and therefore the ones that have been studied the most. Apart from the one by Guerín, who is a great director, but isn’t so well-known, they are also known abroad. Almodóvar is an international figure. L'Auberge Espagnole was very successful despite the director not being well-known. There’s also the interest in the world of Erasmus. Although now for young people it’s completely normal, when it was released and I saw it in the cinema that wasn’t the case. It was something new and revolutionary. Woody Allen and Iñarritu are also very well-known. And Guerín, as I said, isn’t internationally known, but En construcción won a lot of awards, attracted a lot of attention and was very interesting, since it gave rise to a discussion about the city. In Barcelona there’s a master’s degree in documentary audiovisual creation and a huge number of documentary films are made about the city.

A new city can also be built starting from Barcelona, such as Barcelona as L.A., Havana or Paris. How do you analyze the city when it’s not the same city?

That’s not a subject that I’m interested in. It is funny to see how places in the city are used to represent other cities. It’s also an advantage for the film commission to be able to propose parts of the city for this. This doesn’t just happen now; it also happened before, such as in the film Circus World in which Barcelona port was Havana. In the 60s and 70s, not just Barcelona but the whole of Spain was used to represent other cities or landscapes.

Your book begins with a quotation by Montserrat Roig on two Barcelonas that she sees from a bird’s eye view. Do these two cities coexist peacefully?

No. It depends on which period we’re looking at. Now is not a good time, because there’s a conflict between the pretty city, without problems, which in a certain way film also tries to present, when the image has to be sold, and the city where real people live. For example, in relation to the subject of tourism. We’re now in a phase in which the city which was built with the Olympic Games - and not only with that, but many things which have happened and many changes, such as the Forum of Cultures, for example - has also continued to change from the point of view of the image and of what it wanted to sell. Now people are questioning a lot the city that has emerged from all these changes.

After the Olympic Games I think there was a period in which people in general were fairly happy about the changes. It’s undeniable that the city came out winning in tourism, jobs, investment, etc. and now there’s a problem which has to be controlled. But this happens in all the tourist cities in the world. I work in Venice and suffer from it; I think it’s worse than in Barcelona.