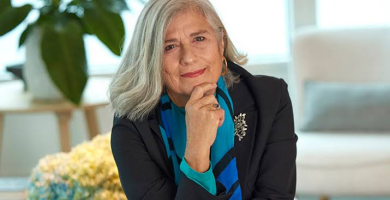

SALIMA JIRARI: "WE WON’T HAVE A TRULY DIVERSE, INCLUSIVE AND RICH INDUSTRY UNTIL THE WHOLE SECTOR AND ITS GRASSROOTS UNDERSTAND THE WEALTH THAT’S BEING LOST BECAUSE OF THE CURRENT DYNAMICS OF THE SECTOR."

This month we interviewed Salima Jirari, a consultant specialized in diversity, equality and inclusion in the audiovisual sector with more than 10 years’ experience in various areas of audiovisual. We talked with her about her job and what it involves.

How did your interest in film and audiovisual begin?

I think it was an instinctive or intuitive interest. A genuine interest from the position of the audience, when you begin to think: “how do they do all that? How do they make adverts? How do they make series? How many people are working behind that?” Maybe even from when I was a teenager. Then there’s a time when you decide whether or not you want to study and then a lot of factors come into play. But I’d say that it was more like a non-rational thing.

You are a consultant specialized in diversity, equality and inclusion in the audiovisual sector. Did you know right from the beginning that you wanted to do this or is it something you came across?

The truth is I didn’t know. And like everyone in the industry, I’ve done a bit of everything. I worked for many years in production; I was in the Barcelona Film Commission for four years. I was eight or nine years in the distribution of various types of content. For a long time I specialized in the acquisition and negotiation of rights and licences.

And when I was working in purchasing or programming, I realized that in a certain way you’re responsible and you often have a certain preference for one type of content and not for another. There are also some stories which make you feel uncomfortable; it’s not a positive discomfort, but rather you say: “there’s something not quite right here, but which I don’t know how to reflect”. And also, above all as a programmer, you realize that you have the opportunity to choose maybe five or ten titles, which will have a visibility that maybe the other hundred that you’ve seen won’t have and the possibility to transform the way people think, to generate a new benchmark, to broaden the audience’s outlook.

That’s when, starting from an individual interest, I began to do a lot of training in everything that intervenes in these decision-making processes, unconscious biases and everything related to this. I undertook this personal training process above all in UK and US training centres. The pandemic also helped me a lot because, suddenly, courses that I’d wanted to take for a long time were online and it was like a dream come true.

I began much more to acquire that outlook and the capacity to understand that, in actual fact, the stories behind all this not only have the structure of the script or that of production, but there’s also a narrative structure which sustains, perpetuates or breaks with a series of stereotypes. From then on I began to receive a lot of consultations, even before defining myself as a consultant. Initially they were from people close to me. A friend who had a script and wanted my feedback. And you do it out of love and friendship, but it came to a time when it was a friend of a friend of a friend. Then you really start to think: “I’ve spent the weekend stuck indoors reading a script”. And you realize that it’s something that has to become professionalized, and it’s true that it’s a role that already existed in other countries; it hasn’t just been invented.

And did you find that you had to do all the training abroad, as you mentioned.

I’ve done many very different training courses, and all in the United Kingdom or the United States. Here there wasn’t any training, or anyone with this role. Now there are two or three of us and we often even share our doubts or meet up because there really are so few of us that it’s very good to be able to network. And I also think that it’s interesting to see that there are more people who are devoting themselves to this, because it also indicates that maybe the industry is increasingly taking this step forward on including these figures.

What does it involve? Could you give us an example of what your job is like? We suppose that you come in right at the beginning of the project.

Personally I work in different phases. I do find it difficult to accept projects, unless it’s a very specific issue, in the rough cut phase, for example. I tend to say no, because I really understand that there’s little room for manoeuvre. Also because often people ask for the consultation thinking that their doubt lies along the lines of “I’d like you to take a look at this because there’s a racialized character”. And, suddenly, on reviewing the project, you see that there’s also (and I’m inventing this) a narrative that perpetuates violence against LGTBI+ bodies and that maybe they weren’t aware of it. Things often arise which aren’t the reason why you initially entered the project. That’s what it involves: really discovering what your project is perpetuating and becoming aware of it. And once you become aware of it, deciding whether or not you want to perpetuate it.

For me, it’s always best to work when the project is still in the development phase. Above all, with initial versions of the script, because there’s still the opportunity to rewrite it, with what the diversity advisor’s told me or what the script editor’s told me. This is also when this work makes the most sense. And you see projects which really change and evolve a lot and, suddenly, they make a radical change. That’s also very nice to see.

What difficulties do you encounter on doing this job? We imagine that if they consult you they are already very receptive, but are they receptive enough?

I think I’d say that I’ve come across mainly two profiles. One which really already senses and has a lot of doubts and says: “I think that this character or this narrative...” Then, when they start with this intuition, you’re already halfway there. The work is very enriching and easy and, when you point something out, they don’t fall back into that.

But also, maybe to a lesser extent, I encounter creators or producers who are more seeking validation. It’s true that if they find that validation everything goes well, but if I suddenly point things out that they weren’t aware of, they become more uncomfortable. Situations like: “well, we’ve already got it all written, we’ll send it to Salima just so that she can confirm that it’s all okay”. Not that it’s all okay, because it’s not all black or white, but to make sure that they’re not slipping up with anything. And if you suddenly point something out, there can be a sort of tension. That’s not what I find the most, but I think it’s a question of these two profiles.

You also offer training and workshops on this. What do they involve? Do you go to groups or individuals, producers? What’s it like?

I do a bit of everything. I work in a lot of residences and laboratories, and on many both national and international development programmes. I offer workshops in these spaces, above all to become aware of unconscious biases. Because these workshops often allow you to see things from another perspective and not from your project. Because it’s often very delicate to come in and talk about the project, that baby that you’re spending so many hours with and that you’re nursing.

The workshops allow you to understand that the creative process isn’t as pure and genuine as you often think. The creative process feeds on a whole series of issues that we carry around in our baggage. These workshops often raise the idea that we should open this baggage and analyse what we have inside. Because sometimes we’re in a creative process and we need something typical, like a robbery, for the plot to advance. Who can commit this robbery? Automatically we all have two or three faces in mind. Why did our brain go to these two or three faces and not to others? It’s very interesting to begin to question this prior programming of how we imagine, create ideas or build them up. Why these faces?

Do these faces interest me because I want to explain, to criticize or to show it in this way? Or am I simply reproducing these faces because I’ve seen them so many times in this character that I simply reproduce it without even realizing? The workshops and training sessions go along these lines.

In a lot of workshops and residences I also do individual work on each of the projects. And I also work with many producers individually, both for script analysis and to work on creative processes, projects for series under development, feature films and others, and also to offer these workshops to the whole team. Above all, they are often provided to executive producers and the leadership or more creative positions. The people who will be in the production, directing and script role of a project. I’ve also occasionally offered them directly to the producers.

How do you think audiovisual needs to change to be more socially inclusive and sustainable?

I think a lot more work needs to be done. Quite a few initiatives are beginning to appear, but I think that they’re the tip of the iceberg. They coexist with a time when many people have the sensation that now everything is diversity. But, despite this, I have the feeling that everything that’s happening, all the programmes that are being held, grants and things like that, ultimately end up being the tip of the iceberg. It’s true that they have a great transformative power, although it’s very limited. In actual fact, we won’t have a truly diverse, inclusive and rich industry until the whole sector and its grassroots understand the wealth that’s being lost because of the current dynamics of the sector.

As regards what needs to be done, I think that, on the one hand, there’s a very biased way of understanding what diversity is and the fact that many places are committed to only putting diversity on the screen. And now, from such and such a place, I don’t just tell the stories that I’ve always told but, suddenly, I’m talking about Syrian refugees, also about what it’s like to be a person with a disability and what it’s like to be neurodivergent. Also, this way of putting diversity on the screen, without being aware of unconscious biases, without really deconstructing ableism, or colonialism, or racism, or how all these things are articulated, means that a whole series of very strong stereotypes continues to be perpetuated on the screen. I don’t think diversity will really change until, for example, there are people on the teams who can offer richer outlooks to the stories so that the stories can be told from different points of view. It’s basically a question of teams and of structure.

This doesn’t mean that only the people who belong to a certain identity can talk about this identity. Everybody must be able to explain everything, but I think that at the moment we’ve only had access to one way of understanding realities. We won’t have the tools to be able to explain a reality other than our own from a different point of view - if no one’s explained to us that this other point of view exists - until we’re able to access and understand the realities from that other point of view.

You are also personally undertaking a project on the Independent Studies Programme of the MACBA which is related to audiovisual.

I’ve actually finished it. I was one of the people selected for this latest edition of the programme, and it’s true that here they select you based on your research proposal. Mine was basically about understanding how the Moorish identity - and how this concept and everything it embraces - is represented or has been represented historically. The programme allowed me to complete part of a research project that I’d like to undertake in greater depth.

You did a short with the Acció Curts programme of Dones Visuals in 2022. Would you also like to be an audiovisual director?

I have my own projects which I’d like to undertake. I have a short that’s being developed with Carla Sospedra and Alba Sotorra as producers and we’re seeing whether we can raise the funding. We obtained one of the Media grants for development. And the idea is to implement it, but the truth is that it isn’t how I make a living. It doesn’t give me a livelihood and it’s also very difficult for me to undertake it. You need a livelihood, and you have to work extremely hard to live in Barcelona. It’s difficult to overcome the insecurity, not just of the industry, but the current general insecurity. I’d love to have many more personal projects and to be able to undertake them, because I have many ideas, but I really can’t afford to.

Going back to your work as a consultant, have you really noted that there’s been an increase in consultations in recent years? Do you note that there is much more interest?

Yes, in my personal case at least, I have more and more requests. This is also because we’re now starting to see people who’ve had very good experience in this process. There’s always a lot of rejection initially when new figures appear. I remember at the beginning with intimacy coordinators, people were saying things like: “now they’re going to tell us how we have to record”. There was a lot of tension at the beginning, and people said: “they’ll make us do things differently” and then they start to see success stories, actresses and actors who explain how it makes them feel more comfortable and calm, how the spaces change, etc. Then this sensation and this good experience begin to spread. The same is beginning to happen with the people with whom we’re doing this type of consultancy. At the end of the day, our industry isn’t that big and people begin to be more committed to this when these good experiences start to be shared.

Photo © Courtesy of the Academy of Cinema - Germán Caballero