MARIO TORRECILLAS: “Agustín was very sick and I was very pleased that the last thing that he did, we did together. It’s something to remember him by for the rest of my life.”

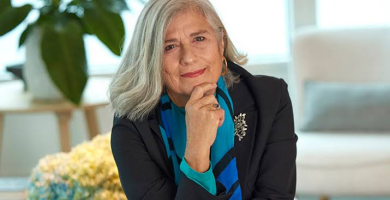

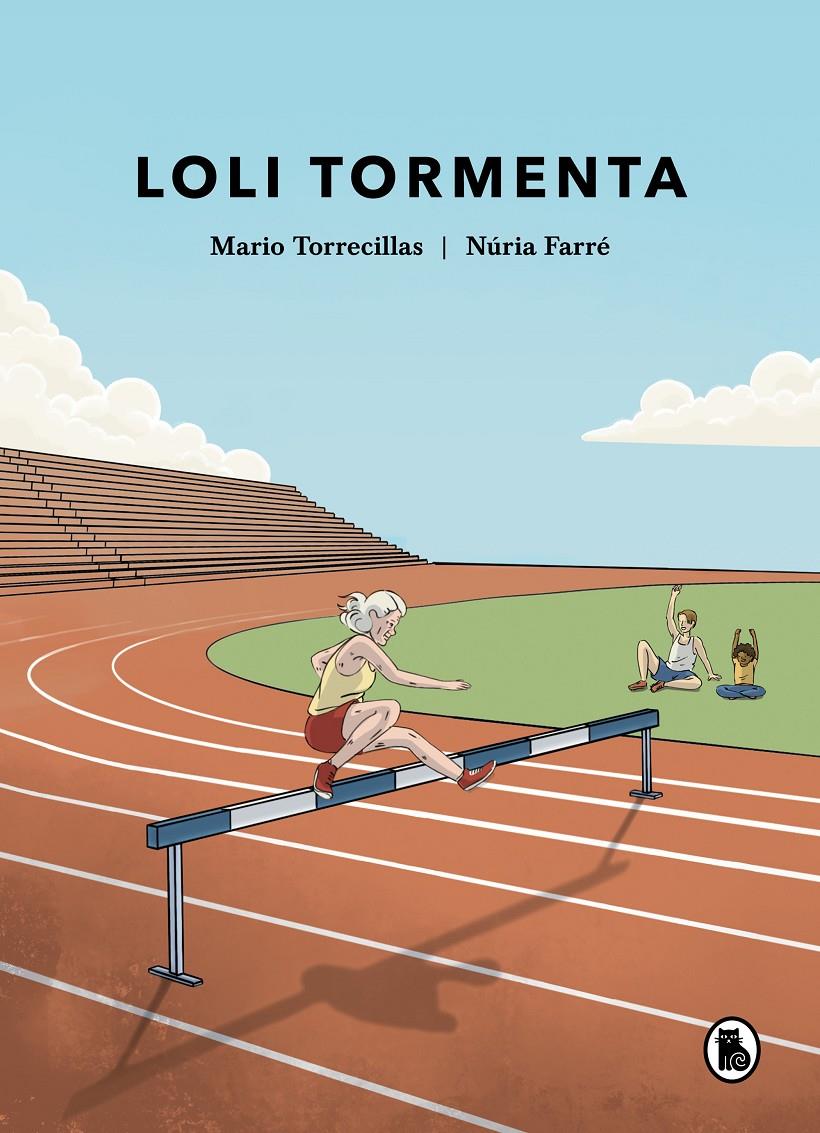

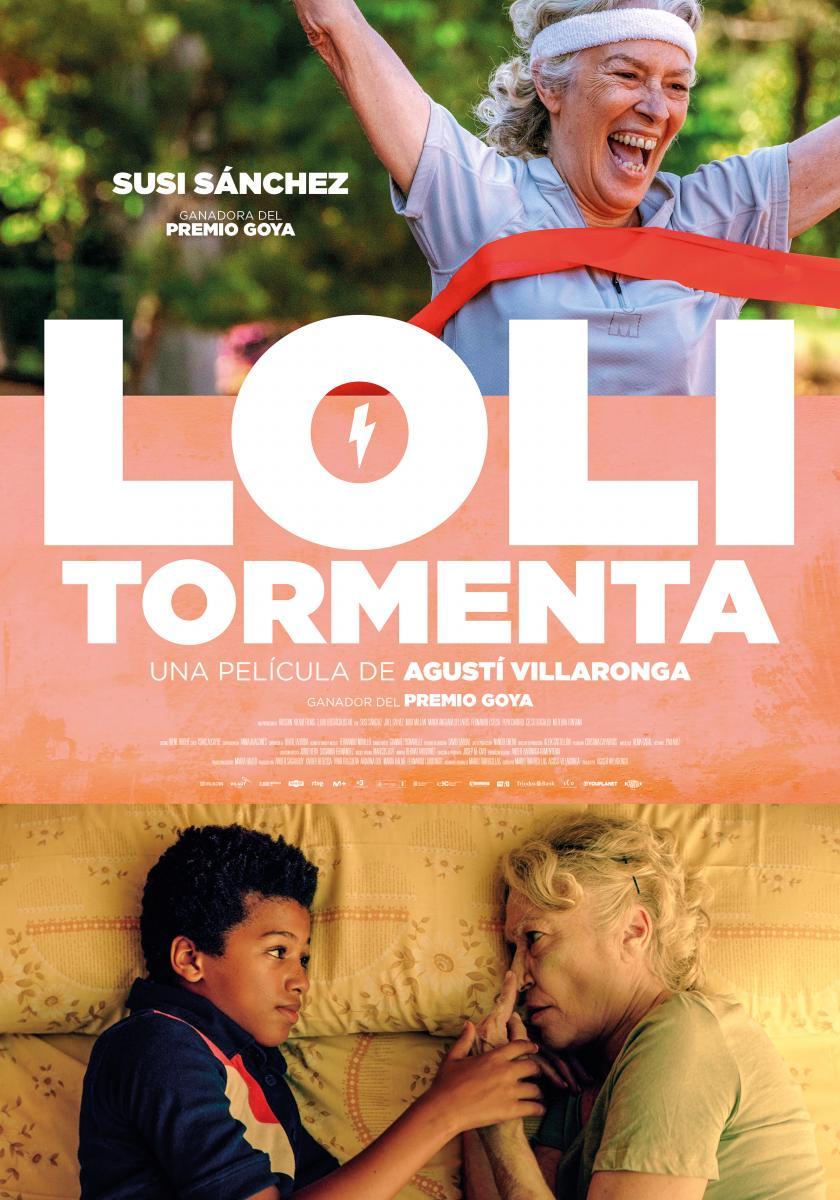

This month we interview Mario Torrecillas, a comic book writer whose works have been adapted to film. We talk with him in particular about the latest film by Agustín Villaronga, Stormy Lola, based on one of his comics.

You shared a flat in Calle Trafalgar with your friend Agustí Villaronga. Right from when you had your first ideas, Agustín told you that he wanted to take Stormy Lola to the big screen. Why do you think he was interested in this story? How did the project of writing the script together come about?

I shared a flat with Agustín for 10 years. In that time I published three comics. He already wanted to do one of them, Dream Team, but in the end it wasn’t possible. They did an adaptation in France which was called Fourmi. But we still wanted to do a film together. One day he came into my studio and saw a load of papers that I had on the wall with some drawings and scenes from what would be the comic Stormy Lola. Then, he said to me: “Mario, I like it a lot. We’ll definitely do this one”. Agustín was very sick and I was very pleased that the last thing that he did, we did together. It’s something to remember him by for the rest of my life. This second part, Stormy Lola, is related to the first part, Dream Team. They are stories of kids to whom something happens in relation to adults and they have to become responsible and change their role. They have to grow up.

Dream Team is the story of a kid who has to deceive his father in order to save him. He tells him a lie to stop him from getting drunk and from sending him to football grounds. Thanks to this lie, his father changes and starts having a different life, being responsible for the child, but through a lie. Although the father changes, the son knows perfectly well that any moment the truth will be discovered. It’s similar with Lola, because it’s a grandmother who looks after her grandchildren, like so many grandmothers in the marginal neighbourhoods, because they don’t have fathers. The daughter of this woman dies. And suddenly, this woman, because of her age, ends up being ill and it’s the kids that look after her. The roles are reversed. There’s a third part which I’ve already written and which is called El tobogán rojo which also closes the circle about childhood.

Agustín wanted to do the first part, which is Dream Team. It wasn’t possible, and then he did Stormy Lola, which is the second part. And he included many things about his life, above all because his mother also died of Alzheimer’s and he knew the disease very well, because he had to look after her. Indeed, the grandmother, who is Susi Sánchez, has gestures which are exactly the same as those of his mother. There’s a scene in which she throws the television out of the window and he actually experienced this with his mother.

As you mentioned, they’d already adapted another comic of yours, Dream Team from 2015, to a French film with the title Fourmi. Did you also adapt the script?

No, this was no less than the Rappeneau family. Jean Paul, the father, is the one who did Cyrano de Bergerac with Gerard Depardieu. Just imagine. It’s a family which has been involved in film forever in France. The son is an excellent screenwriter, Julien Rappeneau, and he did the adaptation. He wanted to offer his vision of the book. I didn’t interfere at all. I went to the shoot because they invited me. It’s moreover a film which cost €6 million, with leading stars of French cinema such as François Damiens and Ludivine Sagnier. It was really nice to see all these actors who had made so many films that I liked such as André Dussollier, who had worked with the main directors of French cinema. And it was wonderful for me to see him there playing a character who had come out of my comic, who I had created with the comic book artist Artur Díaz Martínez.

What was the process of writing the script for Stormy Lola with Agustín like?

I already had the story of the comic quite advanced and then we collaborated on the script for the film. I had the main theme and the scenes done, but then, when he did the film, he came in and worked on certain aspects.

Did being friends help in the process of writing the script?

Agustín and I had a code of stupid things that often occur in cohabitation. These stupid things were really ours. The film is full of these tics. For example, he laughed a lot with phrases such as when the child says: “grandma, the parrot has run out of sunflower seeds”. And whenever I had a month when I hadn’t got much money, I always said to him, “shit, I can’t even afford sunflower seeds”. They are stupid jokes that we made and Agustín couldn’t stop laughing. I called him the big parrot, because sometimes he talked a lot and he was very funny when he started. Suddenly, I’d say to him: “I’m going to have to go and buy sunflower seeds to feed you”. They were our private jokes. Stupid things, which are irrelevant, but which occur a lot when you live together, and the film has a lot of these things of ours.

There is often a great difference between what the screenwriter imagines and what the film ends up becoming. Was it difficult to adapt your own comic to a script? And do you think it reflects the comic well?

It’s amazing how Agustín develops the story on the screen with the scarce elements that he had, because he shot this film in very precarious conditions as regards both filming and his health. I don’t draw; I’m a comic book writer, and I always do it with a comic book artist. I think it’s incredible that the illustrator Núria Farré, who is wonderful, had similar scenes to Agustín without her seeing the film or Agustín seeing the finished comic. They planned some scenes in the same way. This symbiosis is amazing. How two people interpret a text the same as regards planning. If I put: “you see a boy running”, you can do a general shot, a middle-ground shot, in many ways. They both agreed on many shots, the same type of scene. I think this happy coincidence is incredible between an inexperienced artist and an author who has so much weight and who is so big. I think that with time we will appreciate what Agustín left, his filmography, because for so many years there hasn’t been anyone in Catalonia with this level of commitment and authenticity.

Were you also involved in the shooting of the film?

I went to see him a lot, above all because I was concerned about his health. And then it’s true that I was going to see him because Agustín wasn’t well supported. He didn’t have good travelling companions, except for his camera team and the art guy, who is Jordi Vera. I was very worried because he had too many enemies at home.

In the end he was able to do the film, which is what’s important.

I think it’s incredible that he did it because the film is like a metaphor. It’s a grandmother who teaches her grandchildren to jump over athletics barriers. And then the sports barriers end up becoming the life barriers of these kids and it’s astonishing that the film talks about barriers because there was one after another to be able to make it. It was possible to do in extremis. I’m very happy because of that. I would have liked it to be done in a different way. But Agustín, it’s important to say, was also an incredible filmmaker. In two years he made a film as extremely profound and visually complex as The Belly of the Sea and then immediately afterwards he did Stormy Lola and in the middle he had a stomach and oesophagus operation, and then very strong chemotherapy. In the middle of all this he made two films. It’s incredible, in his condition, that he could do all this in two years. He had an astounding commitment and responsibility. When he was very sick, the nurses heard him say things related to films. He was talking in his sleep about things to do with work.

There is one thing that I wanted to say about the shooting of Stormy Lola that I think is important. The outlying area and these kinds of neighbourhoods are never shown on television. It’s very good that film deals with them and more so in the way that Agustín did, in a way full of life, because in general when these neighbourhoods are shown in film, in Catalan and in Spanish, it’s always to talk about drugs and really ugly things. I think it’s really good that there’s a film that talks about the joy of living in a marginal neighbourhood. The sun also comes out for everyone, not just for big cities but also for outlying areas. I think it’s really nice that Agustín showed a marginal neighbourhood in such a relaxed and happy manner, like it really is. And the fact that Agustín went to film in a marginal neighbourhood of Barcelona, but not to show the dark side that films always show. It’s true that the treatment of space is something new in Catalan cinema, because I’m sure that the film that that handsome guy who is also a very good actor, Mario Casas, has made about La Mina will show a La Mina which will cause panic. I’m sure.

Going back to your work as a screenwriter, you also collaborated on the script for the television series Tender Metalheads, didn’t you?

Yes, now the film has been made and it’s been selected for the Annecy Festival. We’re very pleased. It’s the first Catalan film to be in the competition. It was a series and now it’s been edited as a feature film by Joan Tomàs, a collaborator of Juanjo (Sáez). The film is really cool. It talks about marginal neighbourhoods, heavy metal, boys. I helped with the script a little at the beginning.

In 2008 you founded PDA-films (Pequeños Dibujos Animados). How did this project come about and what does it consist of?

It’s as if it was my child. I have a real daughter, very beautiful, and I have another child which is PDA-Films. It’s a small production company that I founded to do animation films in classrooms. They are cartoons made starting from the drawings and voices of the children. They are workshops which end up becoming very modest short films, but we’ve been everywhere to do them. And some shorts have won international awards. An important reward is that the kids learn how to do animation. They do the animation themselves.

What does PDA-Films provide you with as experience?

You’re really enriched by their imagination and their freshness and then by the purity as well. Often when we are already adults we have certain tricks and the kids are very pure and very instantaneous. They have a purity which we gradually lose when we become adults and you connect with this. It’s really nice to see. At the same time you also share what you know so that they can learn. You’re sharing the trade with kids in a free, very creative manner, full of fantasy. Because many of the shorts are pure fantasy.

Do you have any new project in mind?

I want to make the third part of the trilogy. It’s the story of a girl who is very small. I’d love to be able to make the film. It’s a very nice story. And it’s closely related to an episode that my daughter experienced. I really like to be able to tell it through her experience. I think that’s something very new in my life, because I’ve always done it in a different way.