AINIZE GONZÁLEZ: "We’ve made the exhibition like an initial contact so that people who don’t know Maya Deren can understand her and also approach experimental cinema without being afraid."

We interviewed Ainize González, who has a PhD in the History of Art from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and is coordinator of temporary exhibitions in the Calle Moncada site of the Museo Etnológico y de Culturas del Mundo. We talked with her about the exhibition Maya Deren, a cadence of images, which can be seen in the museum until 7 September.

For people who don’t know Maya Deren, who was she and why is it important to talk about her?

She was a fundamental and iconic figure in 20th-century experimental cinema, which began in the 1940s. Her work is very particular. She has been called a dancer, poet and much more. She’s even been called the pioneer of independent experimental cinema in America.

How did you come across Maya Deren?

At university, many years ago. On a course that was called Mass Art and Culture. I remember the lecturer showed us Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) and it was quite a surprise. We had just seen Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou and you had this image of a dreamlike, avant-garde film. So it was by chance, on a course in which I don’t remember what we were talking about, because he didn’t put any more films by her, but it was something to latch on to and I started to watch all her films.

And why did you decide to hold this exhibition at the Museo Etnológico y de Culturas del Mundo?

She’s always been a figure that’s interested me. For me the most well-known aspect was her experiences in Haiti. By chance, many years ago a very small exhibition was held in Switzerland and I thought that Maya Deren would fit in as this figure of experimental cinema, but that we could also analyse these experiences in Haiti and display them and also open up this poetic space. And also open them up to other contemporary voices, such as the Haitian-American writer Edwidge Danticat and Gboyega Kolawole, a lecturer in folklore and comparative literature at the University of Abuja in Nigeria. It’s also important to stress that she gives the movement a certain ritualistic nature.

She was a pioneer in the avant-garde movement. Do you think that women could experiment more, precisely because they were on the fringes of cinema?

It’s true that when you think of paradigmatic cinema the names of men come to mind. And the cinema of Buñuel, even Un Chien Andalou, has a fairly conventional structure. But there are many women in experimental cinema. So maybe yes, the fringes in general give you more possibilities to experiment and carry out tests.

I think men do things immediately and women gradually create them, an analogy being pregnancy. What I mean is that it’s gradually gestated and transformed. I think that it’s a very nice idea to make this reflection: “I make films like the woman I am”. Her films entailed a transformation. Images which changed into others. I think it’s also to do with this frame of mind and also being on the fringes allows you to use different languages.

Dance was also very important for her. Indeed she was a pioneer of choreocinema.

Yes. She was linked to dance previously, because in 1941 she was a secretary with the dancer and choreographer Katherine Dunham on the tour of Cabin in the Sky. During this tour she was fascinated by the sound of the drum, which she then heard again in Haiti. In actual fact, this took her to Haiti. She was also fascinated by movement. Dunham said that she had the conditions necessary for dance even, and that her foot started moving when she heard a drum. So she also had this will, this desire to be able to move. Then she passed this on to the camera. Her cinema has been called trance film. Because of the way the camera moves with the dancer. It’s not something static; it also forms part of the movement. It’s a very particular view which is related to movement and to her interest in dance and again to this ritualistic nature of movement.

How did this interest in Haiti arise?

Apart from a dancer, Dunham was also an anthropologist and carried out studies in dance in the Caribbean. Afterwards she published a book. Maya Deren was influenced by these films and by this material that Dunham had in her archive and also by the anthropologist Margaret Mead and her husband, Gregory Bateson, an anthropologist and biologist. She saw their anthropological film fieldwork in Bali and was fascinated by it. The movements, the films. This overall mixture and the sound of the drum and dance took her to Haiti.

What can we see in the exhibition?

We’ve tried to offer a visual approach to Maya Deren. You’ll see some of her films screened and others with selected frames. We selected specific frames. It all tells the same story. And then, in the final part, there are books, text, quotations and other voices.

Do you think that taking an interest in Haitian rituals and voodoo, which are misunderstood in the United States, prevented her work from becoming well-known?

It didn’t harm her. When they went to Haiti, she and her husband, Teiji Ito, who was also a musician and composer, even learnt to play the drum and then took the music to New York. They held parties with Haitian music.

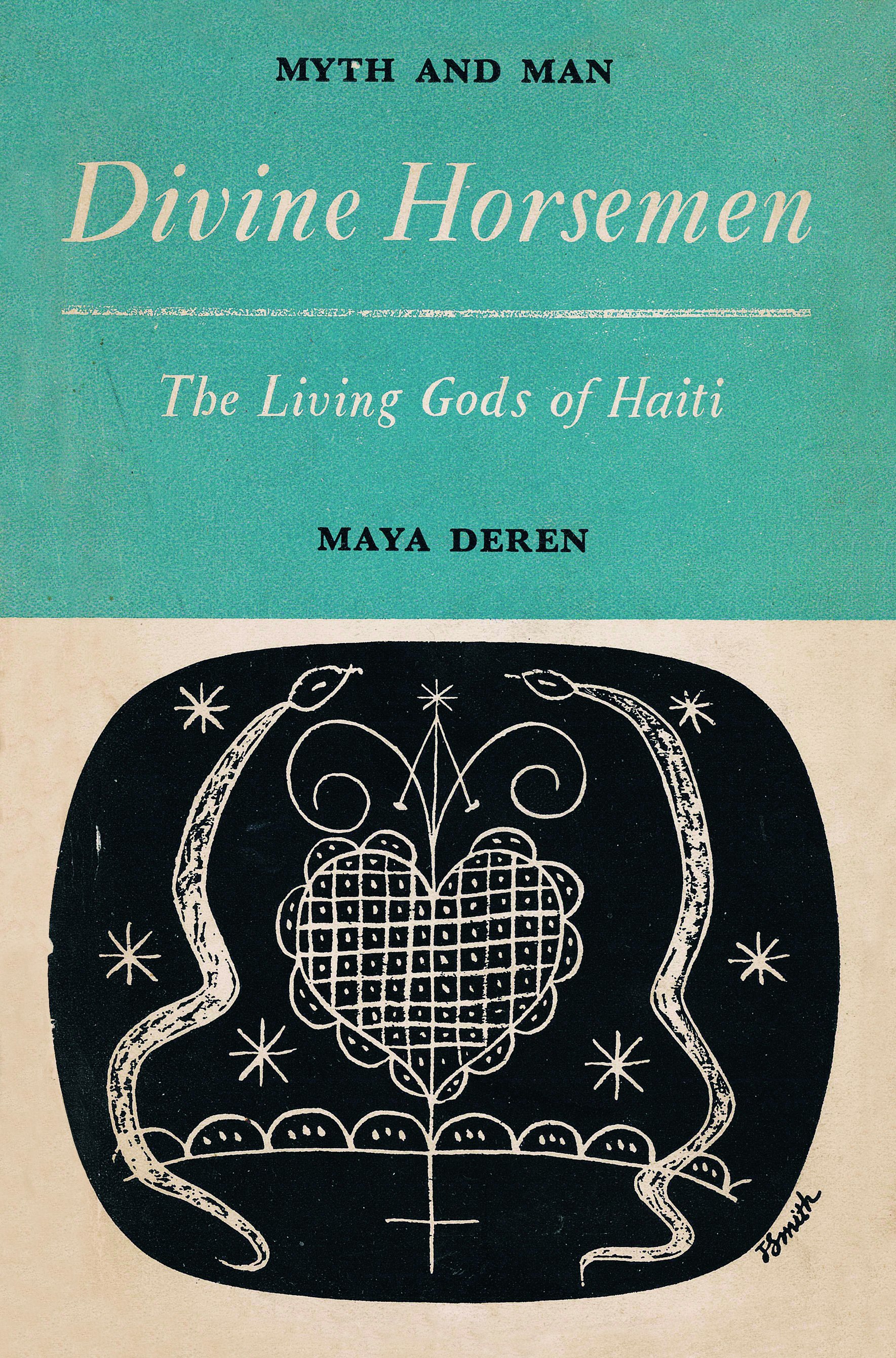

And her book Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti was very successful. It’s true that it’s a book which is very poetic and personal, but it has a sound basis. It was documented from an anthropological perspective. It’s also been translated into other languages. It’s not in Spanish, but it did well and was reprinted in Italy and Germany. In the second edition, her publisher, Joseph Campbell, is very supportive of her particular methodology, but it’s a book that was very successful and it didn’t harm her.

At the time she was very well-known. She was even the first woman to win the Grand Prix at the Cannes Festival for Meshes of the Afternoon. The fact that she was so successful makes it even more curious that she’s no longer well-known.

Absolutely. Maybe it’s related to the fact that she died very young. Maybe not. She was also a woman and that has an influence. It was very difficult for her to find funding for The Very Eye of Night (1958), which was a very important project. She was always fighting. And defending herself, giving classes at universities to explain her cinema. She wanted people to see the films, and there were even some unfinished ones, like Medusa (1949), which was an exercise that she did with students but didn’t finish. This teaching aspect was very important for her.

And does she talk much about her creative process in her writing?

Yes, she reflects on this. She has a particular type of writing. And there are also audios, a documentary called In the Mirror of Maya Deren (2001, by Martina Kudlácek), also with extracts by her. She talks about it in her book An Anagram of Ideas on Art, Form and Film. The text is very curious, very characteristic of her. In it she reflects a lot on cinema.

What process did you follow to create the exhibition?

It was clear that we didn’t want to focus just on the finished films; we wanted to see the whole figure and also the part related to Haiti was very important, especially as it was in this museum. We said: “We can’t put all the films”, although there aren’t that many, you know? So I met the designers, Anna Alcubierre and the graphic designers, Lali Almonacid and Marta Llinàs, and I developed a script. Deciding: “It’d be good to screen this film, to show frames from that one”... So I downloaded all the frames and made a selection. I transferred them because for me it was very important to capture this sense of movement, the poetic, ritualistic sense. I also wanted it to be choreographic, not just static, not just film, but also still images. And I wanted to provide a sort of visual contextualization for people who didn’t know her. I also wanted the Haiti part to be archival.

We found the language all together, starting from the content. Anna’s first idea was to do something that can be moved, that people can see as if they were film posters with this choreographic element. What you normally do in the cinema is to sit down and watch the film, but as this was an exhibition we thought it’d be very interesting for people to move. Apart from evoking this sensation of movement that she created, we wanted them to experience it in a different fashion. We thought that visually it was a good way for people to get to know her. Fitting it together and finding a link between the visual aspect and the content that we wanted to transmit

And how did you select the final part, with these other voices?

I thought of the writer Alejo Carpentier who wrote The Kingdom of This World, which is a paradigmatic book which offers a harsh, but fantastic portrayal of Haiti. And it also fit in with the 1940s because Maya Deren was awarded the Guggenheim Fellowship in ‘46 and in ‘47 travelled to Haiti, and Carpentier travelled in ‘43 and published the book in ‘49. And also because he was a musicologist, and we were showing Maya Deren’s interest in Haitian music.

We thought of another artistic language, Jacques Tourneur for the film I Walked with a Zombie. I think it’s also important because it was a completely different approach to Haiti. He didn’t go to Haiti, but he started from the text written by Inez Wallace and published in an American magazine about a trip that she made in search of a zombie. We were also interested because it was a voice from the 1940s.

Edwidge Danticat was because of that wonderful book, which begins with the quotation by Maya Deren, Create Dangerously. The Immigrant Artist at Work. And then, within the story that we’ve reproduced in the catalogue, she talks about Basquiat, the Haitian painter Hector Hyppolite, voodoo, popular art, cultural identity... All this fits in very well. We talked with her about including this story and she said yes. A contemporary voice from Haitian literature, although she migrated to the United States, but we thought it was interesting to offer a contemporary perspective on Haiti.

And then Gboyega Kolawole. In the catalogue we also have this text on the Yoruba religion and the hybridization of Haitian practices. We thought that it’d also be interesting to have a contemporary voice to talk to us about one of the roots of these practices, which is Africa. They are different voices, different motives, but it was all connected.

What else do you think should be done, apart from this kind of exhibition, to revive the figure of Maya Deren?

That’s a very difficult question. To tell the truth, I don’t know. Because her films are already programmed and shown in cycles. It’s happened in Xcèntric, at the University of Girona as well, a cycle was held recently in Valencia, also with dance. Even from different disciplines, but I do think something should be done to remember her because she’s a very interesting character.

She didn’t make many films because she died very young, but I think it’d be good to publish more things about her. Now we have the catalogue in Catalan and Spanish, although the texts talk about Haiti. It’s true that there isn’t much in libraries. The two biggest books of her writings that we have in the exhibition are from the University of Barcelona library, another is from the Tàpies and the majority are mine. It’s true that there isn’t much when you look, not even in bookshops.

The designer said to me: “Ainize, we’ve revived Maya Deren”. It’s a small thing so that people who don’t know her can also gain an insight in a simple and different manner.

Film schools would be ideal to carry out visits.

Yes. We have a text in the catalogue by David Martínez Fiol, who also lectures on the History of America at the Autònoma. We also had to contextualize colonization, taking slavery, the independence of Haiti and also the context of the United States when Maya Deren was there.

The exhibition is also quite experimental. A little like what she did. It’s fragmented, with small symbols that you can gradually pick up. We don’t have a very big space, but we’ve made it like an initial contact so that people who don’t know her can understand her and also approach experimental cinema without being afraid. And for the first time we’ve also opened up to mass-appeal cinema, in a certain way, in the museum.

For me Maya Deren is a very interesting figure, for this unfinished aspect. She also says that her works are unfinished, fragmented, speculative, even contradictory, that they have a space in which to breathe, which we need so much. These spaces which allow you to look at things in a different way.