MIQUEL ÀNGEL PINTANEL: “Until the 50s or the beginning of the 60s, the still image was like a parallel film.”

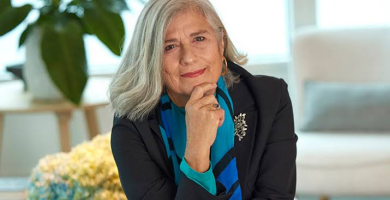

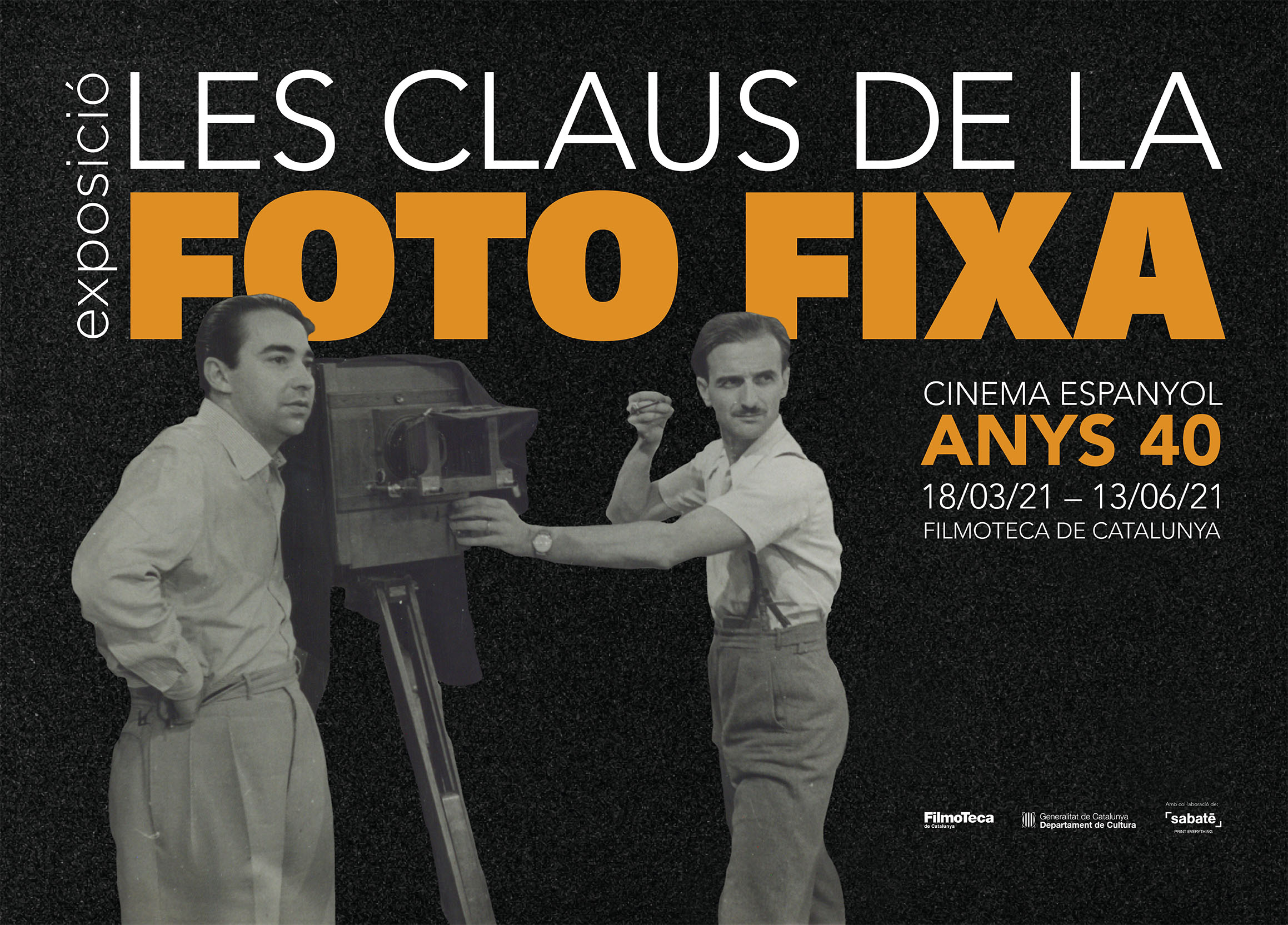

This month we interview Miquel Àngel Pintanel, documentarian specialized in photographic archive at the Filmoteca de Cataluña (Film Archive of Catalonia) and curator of the exhibition "The keys to the still image: Spanish cinema in the 40s", which you can see at the Filmoteca until 13 June. We talk with him about the exhibition, about his profession and in particular about still images.

Tell us a little about what you do at the Filmoteca de Cataluña. How many years have you been working?

Since 99 and I already began dealing with the photographic collection of the photo library. First in the film archive, which is where it was previously, and now in the Raval, in the headquarters of the central Filmoteca which is where we have all the stocks. Which is not cinema, as the cinema collection is in Terrassa. Above all, what I do is to classify the photographs. Since we have so many, we have begun with Catalan cinema, then Spanish cinema, and when we can we will finish the part on European cinema. We always say, as a joke, that the Americans will have to do their own, as they have much more means.

How did your interest in photography begin? And why did you decide on this profession?

I studied history of art and specialized more in cinema. I began to work at the Filmoteca, through this connection with cinema. When I began they offered me the photographic collection, which is obviously still images, but which is closely related to cinema. From then on, my specialization was through practice. It’s actually only a small change. The film director Robert Bresson explains an anecdote about this. The film that he was making wasn’t going very well and he asked the still photographer: “How is your film going?”. In essence, until the 50s or the beginning of the 60s, the still image was like a parallel film.

For someone who doesn’t know what it is, what does it mean when we talk about a still image?

We actually have a problem. In Spanish the same word is often used for different things. The word foto fija can refer to the person who takes the still image, that is the still photographer. It also describes the product created and even the profession. When we talk about a still photographer as a profession it is easy to distinguish, because it is a photographer who was hired during the shoot and who did various jobs. The main one is obviously to take the still images, but there are also others. For example, before the shoot. In preproduction they take photographs of the decor to see what it will look like on the screen. But their main job, at least in the “golden” age, the 40s and beginning of the 50s, was to take photographs of the shoot. Not while they were shooting, but in the breaks. When they had finished shooting a scene, the actors and the technicians were told to pay attention to him in order to take a photograph which was similar to the film, but which often wasn’t exactly the same as the film. These photographs are the still images.

The still image often explains a different story. Is it maybe another vision of the film as you mentioned with Bresson’s anecdote?

Rather than a different vision, what they have to do is a summary of the film. For example, films are usually shot with close-up shots, one shot at a time, one person is talking. Often in cinema what is done is to explain this with different shots or moving the camera. What the still image often has to do is to put one sequence or even two in a single photograph. They do something which is different from the film, but which always has the reference of the film.

What is the Filmoteca’s still image collection like?

We have almost a quarter of a million photographs, above all negatives. We do have the occasional positive collection, but the majority are photographic negatives. The majority are the photographs that the producers left in the laboratories when the film was made. It is a pleasure to have them, but it’s also a bit sad because it means that the producers left them in the laboratory.

Didn’t they consider them to be important?

No. Because cinema was in a way something which was disposable. The film was released, re-released, went on what is called the provincial circuit and then ended its commercial run. When video and above all cable TV began to arrive it did have a longer run, but at that time, they made the film to be exploited for two or three years, they forgot about it and they made another film.

What type of users use the Filmoteca’s photo library collection? We suppose that there are professional and non-professional users.

It’s changed a lot now. Some years ago they were only historians or very specialized people, also sometimes people who were creating publications, those who were making documentaries if they couldn’t find films they tried to see if there were any photographs. What is good now is that with digitization we have a digital repository in the Filmoteca and everyone can access it. This is disseminating the collection much more. Also, with the exhibition, there are many people who are discovering that there are photographs in the Filmoteca. People think that we only have films, but there is a lot more: museum objects, promos, stamps, posters, ... There might be 900,000 objects in the collection, apart from the films.

Does the Filmoteca come close to your idea of an ideal photo library or are there still things to be done?

Sometimes you shoot yourself in the foot and think that there is still work to do, but when we go to congresses or meetings of film archives, we see that the majority treat cinema, the film part, the actual films, very well. But all this photo library part, personal archives, ... We are one of the film archives, maybe not in the world but at least in Europe, which treat this part the best. And of course in Spain. Obviously you can always improve. You would like more staff, more tools, more of everything. I don’t want to boast, but we are quite happy in the Filmoteca de Cataluña.

You are also the curator of photography exhibitions. How do you show this collection in an exhibition? What is your work in this case?

There is obviously the work which began years ago, because if you don’t classify it you can’t disseminate it. First you have to decide what part of the collections you want to display. We started five years ago with an exhibition on the 30s with photographs from the “Reproducciones Sabaté” collection, which is one of the most direct and very closed collections, since the producer left the material there. It is therefore very easy to work with it. After the 30s, we continued chronologically. We are now with the 40s. Once you have decided which part you want to show, you have to choose the photographs. Not doing it from the most beautiful photographs, which would be the easiest option, but rather trying to see what links these photographs. One of the things we have tried to do is for the photographs to have some common link. Despite the fact that this is sometimes difficult, because one is interesting because of the composition, but also because of the lighting. They also have some point of interest. In this case, I think we had 3500 photographs from which to choose and from these you have to choose those which you can display. I would always display more, but I suppose that people would go mad with so much photography.

What are the main difficulties that you might encounter on curating this exhibition?

One of the biggest is what I was telling you: restricting yourself. When the collection is so interesting, you would display it all and that’s not possible. Then another is a result of what still image work was like and how it declined. There is very little information about the actual photographers. We call one of the parts of the exhibition “The dark side of the still image” because unfortunately one of the things about which we know the least is the life of the still photographers. There was also the added difficulty that in 2020 I had to go to different archives to seek information on still images and we were affected by a pandemic in the middle of it all. We would probably have more information if I had been able to investigate in 2020. I went to the Filmoteca de Madrid in February; I was supposed to go back in March, but of course it wasn’t possible.

It’s interesting that there isn’t much scientific bibliography either. This often happens when a field falls halfway between two disciplines. It’s very difficult because it comes between cinema and photography. So the person who is going to do research has to have knowledge of both. For example, there’s another discipline which is cinema music which has found researchers to research it, but as regards the still image it has not been interesting enough for those from photography, or for those from cinema.

Emili Godes, Salvador Torres Garriga are still photographers. Very little is known about them. Are they the great unknown?

Not all of them, because they did other jobs. For example, from among the important ones, Emili Godes was known as a photographer. Salvador Torres Garriga was a very important director of photography. And there is another case about which we have more information because it is quite curious. Valentín Javier, who was a producer, writer and did a thousand other things, also occasionally worked in still image. We know things about him, but not as a still photographer, but rather for the rest of the jobs that he did.

Were there any women?

Not in the 40s. There were starting from the 50s. I think that Joana Biarnés began in 56; she was a pioneer in press photography and also in still image. Then there were a few women, but again we have little information about them. We have more information about some, such as Montse Faixat or Colita who we know better, but they came later. They began starting from the 60s. And if the male still photographers are unknown, you can imagine what it’s like for the women. Except for Joana Biarnés, Colita and Montse Faixat, who did other things, it is very difficult to find information about the majority.

Now in the Filmoteca we can see the exhibition The keys to the still image: Spanish cinema in the 40s. You mention that this was the golden age of still image. Why was that so?

This was really the last time that you could take photos very calmly. Starting from 51 cinema began to change a lot. They began to do outdoor shoots, more naturalistic films. The way they made cinema changed a little and, obviously, so did the way they made still images. In the 30s, which is the other period that we dealt with in another exhibition, the photos were already very good, but you can’t see what you can see in the 40s such as triangle compositions, ways of using painting tools... A whole series of things which, if you don’t have even just two minutes to do them, you cannot do them. And two minutes is a long time on a shoot. Because the shoots are madness. Also, apart from the industry, there are technical reasons and one of them is that the material that we have is 18x24 photographic plates, which are those typical big cameras that people go behind and cover themselves to look. With these cameras, you can’t just go there and take the photo. It’s a different way of working. Also, starting from the end of the 50s, instant photography began, which greatly changed the panorama and, therefore, the 40s can be considered as the golden age of the still image.

Is it very different now from what it used to be? Maybe it was more of an art before.

There are very good photographers now as well, but the way that they have of working is during the shoot, not during a pause. Some photographs are still taken like before, for example for the poster. From the 40s we might find that in one of the boxes we have there are 48 photographs. Forty-eight photos on a shoot taken during the pauses are a lot of photos.

What will we be able to see in the current exhibition? How have you divided it to explain still image in the 40s?

We have produced a more educational part at the beginning of the exhibition. To be able to do this, we first compared with the films, putting four screens where you can see different ways of converting the film into another type of material. There is a very simple one to resolve the one shot at a time that we talked about earlier. And there are others where you can see how the still image adds characters to the photograph who do not all appear together in the film. There is even a more extreme case which combines two sequences in the same photograph. The following part is to compare it with its main reference, apart from cinema, which is painting. To see how they are composed, we have put the composition lines on the images, so that people understand how it was done. I have seen this on some guided tours. People know that the photos are very good, but they don’t know why. One of the things which explain this is to see what the composition is like. For example, when there are people in the photograph, they look at each other. And if you concentrate you see that the characters are related to each other thanks to where they look. These are little things which we might sense, but we have tried to explain them. We have also talked about depth of field, about the way to illuminate. And then, starting from this first sphere, there are the photographs to see how they would normally be seen in an exhibition, more freely, but so that you can apply what you have learnt before. Sometimes the general population lacks visual culture. There should be more exhibitions to explain these things to us.

Lighting also plays an important role in the arrangement of the material.

The way you illuminate is very important with still image, so we also tried to reflect this. When you enter, you will already see that it’s a very bright exhibition, even quite a bit more than the average one. We tried to make it a bit darker when you reach the part with the still images, because, as we have said, this is unfortunately the dark part of still image. And, at the end of the exhibition, we have a small camera obscura, which you can’t normally see, with the photographic negatives. The material which made the still images. This was also good for us to preserve the negatives, since they could not be well lit up. They are damaged with light. It has a poetic part, but also a practical part. You have to be very careful with the light. Normally, you can see this more in an exhibition of pastels or of more delicate painting which is always darker. The poor photographs also have to be in the dark.

You also offer guided tours of the exhibition.

On Wednesdays. I do them myself. At 12, at 4 and at 6. I like doing the guided tour, first because I enjoy it, but also because I learn a lot. There are different points of view and there are things that you would not focus on and that people who are sometimes novices make you see. Because they ask a question which is obvious and which you haven’t seen despite the fact that you have seen the photographs hundreds of times. Or you know it, but you have never explained it until they ask you. For me it is fantastic to give guided tours. You just have to register on the Filmoteca website sending an email.

What will the next exhibition be?

We’re not preparing anything yet. The Filmoteca will do some more shortly, but not about photographs of its archive collection. It’s a job which has to be like a ripe fruit. You have to do the exhibition when you have already classified, and not just that, but when you have reviewed the photos, you know the material that you have. These are things which take time. For example, to do the comparisons with the films, you have to see the films calmly and compare with the photos. You can do the exhibition when the fruit falls from the tree.